Understanding how disputes arise

This page explains how all disputes follow a life cycle or pathway and provides a series of questions to help you analyse the types of issues.

On this page

Disputes follow a pathway

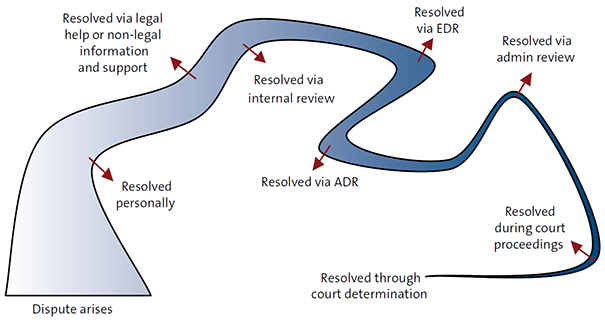

All disputes follow a life cycle or pathway. They will start when an issue or concern arises. These matters may become a complaint, which then escalates into a dispute.

A dispute will generally arise where there is disagreement over a fundamental aspect of the complaint, or when the redress that is offered does not satisfy the complainant.

There will be various opportunities along the way to resolve the dispute — personally, informally (eg, negotiation or mediation) or formally (eg, tribunal), or it may be left unresolved.

Some disputes may go through several dispute resolution processes, and a few will progress to the formal court system.

Dispute pathway showing how the number of disputes reduces as the methods of dispute resolution become more formal

The volume and timing of issues

A key first question is how many issues are arising. A party, or group of parties, may also commonly have more than one issue or concern. Understanding these trends over time is important for determining the size and scale of the response required. This will include how long it normally takes for issues to come to light and whether the incidence of disputes is falling or rising.

What the issues relate to

Not all issues that come to the attention of agencies should be automatically treated as complaints or disputes eg, the issue may simply be an inquiry to clarify a matter or provide further information.

Some issues that are raised through a complaint can be settled before they become a dispute. This can involve the recipient of the complaint accepting responsibility and taking action to resolve the matter or make amends. For example, an admission from one party that it was at fault and an apology may be an option for early resolution. The complainant may be satisfied with this response and choose not to take the matter further.

A party may also raise an issue that does not require a dispute resolution approach.

For example...

A landlord may lodge an application for tenancy mediation concerning rent arrears, not because there is a dispute, but for the purpose of facilitating prompt payment. When it was found that a significant proportion of tenancy disputes related to non-disputed rent arrears, the GCDR helped to develop a fast track process for these claims that does not involve a full mediation. This has made the process much more efficient and quicker for the parties and reduced the costs for the mediation service.

Issues that concern matters of fact or law

Many disputes arise because there is a difference of opinion between the parties about factual matters, such as what happened. Other disputes arise because there is disagreement about the parties’ respective rights or responsibilities under the law.

Disagreements over whether a particular expectation is a legal requirement are generally a question of law (eg, am I required to complete a tax return?). Whether specific legal requirements have been met may be a matter of fact (eg, does the tax return I completed supply the correct information?).

Issues that involve rights or interests

Disputes can arise when someone feels that their rights have been marginalised or breached due to action or inaction by the other party. Rights may be socially recognised (moral) or formally established in law or contract (legal).

At a basic level, the interests of the parties are the things that really matter to them. Disputes may arise when their interests, including the needs, desires and concerns of the parties are not aligned, or are in conflict.

Issues that relate to technical matters or interpersonal issues

Disputes can reflect professional differences of opinion or interpretation. They can also represent the breakdown of a professional or personal relationship.

For example...

Two engineers may have different views on whether an earthquake damaged house should be repaired, or replaced with a new house. Alternatively, they may disagree on the extent or type of repairs that are required for the house to be restored to its former state.

Business partners may lose trust in each other and want to go their separate ways, but disagree about what assets each is entitled to, or a husband and wife may separate and have different views about the custody of their children or how to divide relationship property.

Key questions to analyse issues

- What is the volume and number of issues per party that you are dealing with? Does this fluctuate over time?

- Do they relate to a complaint, or something else (eg, an inquiry)?

- Do they involve matters of fact or law?

- What rights and interests are involved?

- Are the issues technical or relatively straightforward?

- Do they involve interpersonal relationships?

Next steps

The next page in this guidance is Understanding the parties to disputes.