Offshore renewable energy in New Zealand

Offshore renewable energy is energy generated from a renewable source, such as wind, sunlight, waves or tidal currents, using developments located in, on, or under the sea.

On this page I tēnei whārangi

Some information on this page is subject to the Offshore Renewable Energy Bill becoming law.

Why offshore renewable energy matters for New Zealand

The Government wants to diversify New Zealand’s energy supply to deliver affordable, reliable, and sustainable electricity across the country. Offshore renewable energy is a large, untapped resource that can produce electricity on a large scale. Developing it could help grow New Zealand’s economy while providing clean, sustainable electricity.

How offshore renewable energy supports our energy goals

Over 70 percent of New Zealand’s energy use in 2024 came from non-renewable sources.

Energy in New Zealand - Overview

Offshore renewable energy will:

- help reduce our reliance on non-renewable energy sources such as fossil fuels

- support net-zero carbon emissions by 2050

- help to meet growing energy needs

- improve our energy resilience and independence

- enable greater electrification which plays a key role in decarbonising our energy system and supporting the transition to clean energy.

Types of offshore renewable energy

The Bill proposes that offshore renewable energy can be generated from:

- Wind

- Waves

- Tides

- Ocean currents

- Light or heat from the sun

- Rain

- Geothermal heat.

How offshore renewable energy is used around the world

Offshore wind is the most advanced offshore renewable energy technology and at present the most proven and cost-effective at commercial scale.

Many countries, including China, the United Kingdom, Germany and Denmark have operational offshore wind farms. Others have projects which are progressing but are not yet operational.

Worldwide there is over 83GW (83,000 MW) of offshore wind generating capacity already in operation.

Offshore wind installed capacity reaches 83 GW as new report finds 2024 a record year for construction and auctions(external link) — Global Wind Energy Council

China recently constructed an offshore solar farm, and other counties have explored and tested other technologies, such as wave and tidal energy, and are progressing towards commercial scale operation in the near future.

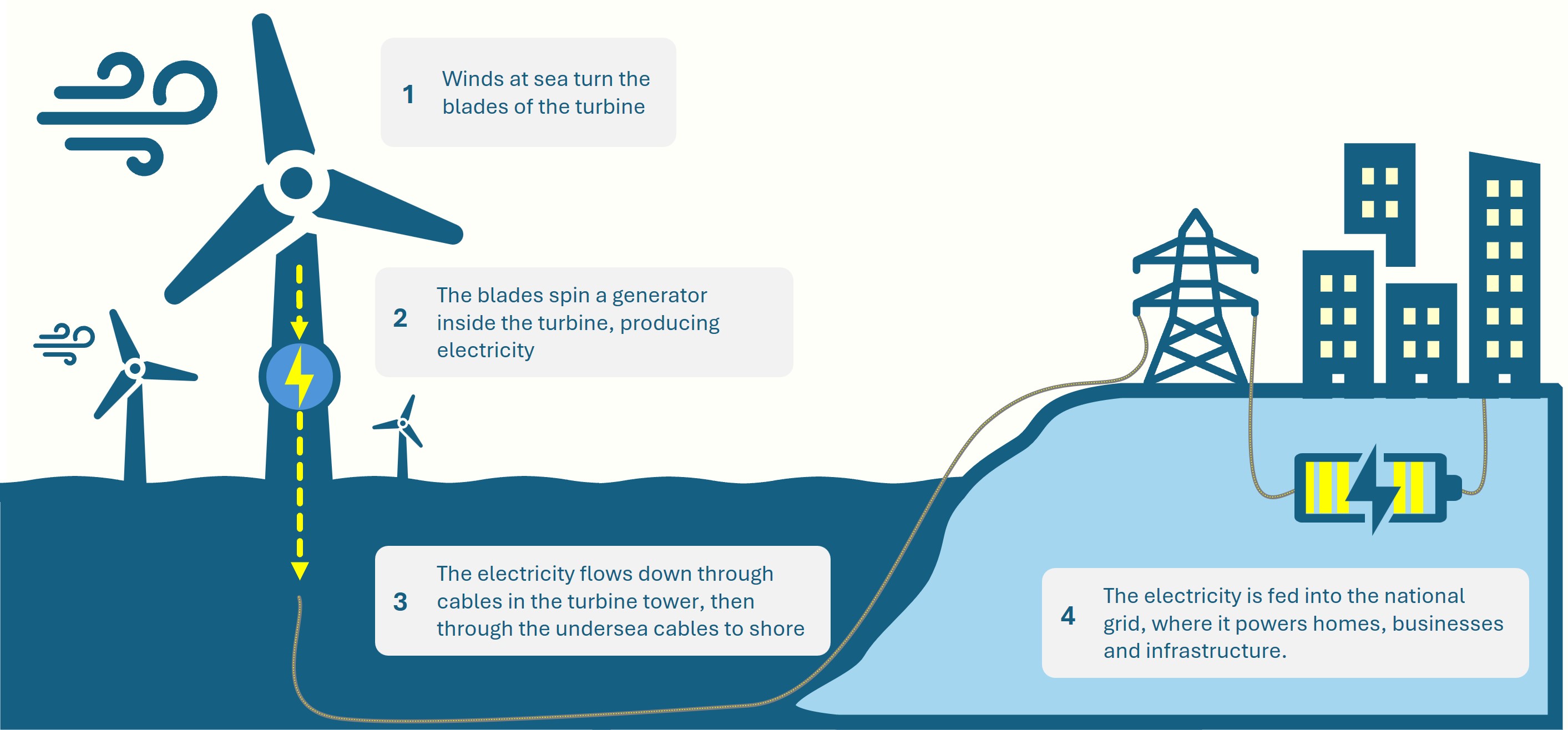

How wind turbines work

Wind turbines convert wind energy into electrical energy in the following way:

Text description of graphic: How wind turbines work

Why New Zealand is well suited to offshore renewable energy

New Zealand has excellent conditions for offshore wind farms due to high average wind speeds.

New Zealand also has a large exclusive economic zone (EEZ) with 96% of the country’s territory being sea, so there is lots of space for offshore renewable energy.

Offshore versus onshore wind farms

Offshore wind farms can generate more power, more of the time, than onshore wind farms due to higher and more consistent wind speeds. The lack of land features and their much larger size, enabled by being far out at sea, contributes to this.

Offshore wind turbines also have lower visual and noise impacts, given their distance from land.

New Zealand has had onshore wind farms since 1997. As of November 2025, there are 21 operational onshore wind farms with a total installed generation capacity of 1,263MW. This generates enough electricity to supply over 553,000 homes a year.

More onshore wind farms are at various stages of the consenting process.

Operating Onshore Windfarms(external link) — New Zealand Wind Energy Association

Environmental and regulatory framework

See the Overview of the offshore renewable energy regime webpage.

Overview of the offshore renewable energy regime

Protecting marine ecosystems

When planning and developing offshore renewable energy infrastructure, developers will be expected to adopt international best practices to assess, protect and even enhance marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

The feasibility permit period gives developers time to study potential environmental impacts, find ways to reduce them, and obtain the necessary resource or marine consents.

Safety Zones

During construction or operation, the Minister may declare temporary or permanent safety zones to protect people and operations.

Some types of offshore renewable energy infrastructure may permanently limit access for some sea users. This will be considered when feasibility permit holders apply for resource and marine consents.

Experience from countries like Scotland suggests offshore wind farms can usually be built in ways that allow them to coexist with most commercial and recreational fishing, marine traffic and other ocean users.

Engaging with Māori

Read about what developers need to do before applying for a feasibility permit and how we engage with Māori.

Public consultation and identifying existing rights and interests

Learn about our public consultation process and developers’ obligations for managing existing rights and interests.

Public consultation and identifying existing rights and interests

Economic and investment potential

Energy resilience

Offshore wind farms generate renewable electricity at a scale that means they are generating electricity more often than not, especially when compared to land-based options, such as onshore wind or solar. This makes offshore wind less intermittent and more consistent.

Economic growth and regional development

Offshore renewable energy projects support economic growth and regional development, both during their development and once they are operational. These enable existing industries to decarbonise and expand, while also encouraging future-focused industries to establish themselves in New Zealand.

Funding model

Applicants for offshore renewable energy projects will be responsible for raising the funding needed to develop and build their proposed infrastructure. The Government will not provide financial support at any stage of the project.

Levies and royalties

The Bill proposes a user-pays system for offshore renewable energy projects. This means the cost of government staff time spent assessing permit applications and managing permits will be recovered through an application fee and an annual levy paid by applicants and permit holders.