4. Problems in the building consent system

On this page I tēnei whārangi

The building consent system has long been faced with complaints of inefficient, inconsistent and ineffective decisions and processes. These typically involve frustrations with delays and inconsistencies and result in finger-pointing about poor-quality work and decision making.

Accounts of problems with the system from interview respondents related to a range of issues. These were often interconnected and included themes related to:

- the size and capacity of the workforce, such as the ability to recruit or engage suitable workers to undertake consenting or building work

- the skills and capabilities of both BCAs and the sector, such as understanding of requirements and level of competency when carrying out regulatory functions

- the behaviours of those who interact with the process, such as the way people carry out their roles, and the relationships between people in the building consent system.

In addition, there were some complaints regarding process-related issues that are leading to frustrations with the system. However, these are not seen to be directly contributing to concerns about efficiency, predictability or effectiveness.

4.1 Workforce constraints are an issue throughout the sector

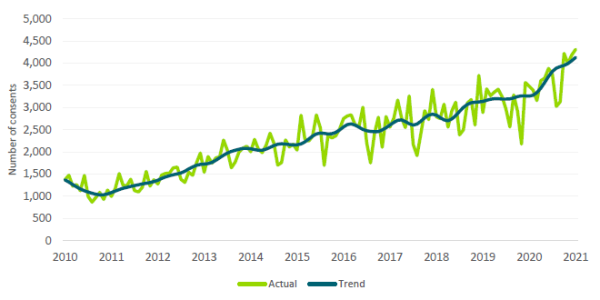

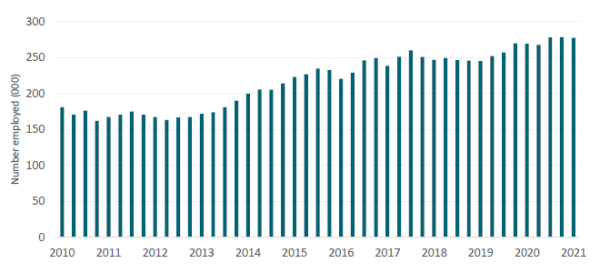

After seeing a significant decline through the Global Financial Crisis, the sector is currently experiencing a sustained period of demand and is now facing challenges meeting its resourcing needs. While the number of dwellings consented has risen more than 200 per cent between June 2010 and June 2021 (see Figure 2), the number of people employed across the sector has only risen by around 50 per cent over the same period (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Number of new dwellings consented, monthly (June 2010–June 2021)[10]

Figure 3: Number of people employed in the construction sector, quarterly (June 2010–June 2021)[11]

Nearly all the participants in our fieldwork identified capacity constraints across the sector as a major issue. Developers talked about significant challenges finding capable and experienced sector professionals as most are already booked out for quite some time. Many professionals confirmed that they were juggling multiple projects and sometimes taking on more work than they can effectively handle.

Capacity was considered a big issue by BCAs as well, with many pointing out the substantial increase in the volume of consenting work they are expected to carry out. Some BCA respondents said that they struggled to meet the statutory timeframes for processing consent applications not because of the time required to assess the application, but because of the backlog of work to be cleared between receipt of an application and its review.

BCAs face competition for skilled BCOs from other BCAs and the private sector

Although many BCAs are actively seeking to recruit and invest in new staff, they noted significant constraints in meeting immediate needs due to the time required for BCOs to achieve sufficient training and experience.

“We can pull someone off the street but we still have to train them on regulations – this is a two year programme that is going to take them out of the office for at least 50 per cent of the time.” – BCO

These challenges may be encouraging the “poaching” of competent BCOs away from BCAs, a practice that was said to be impacting a number of BCA respondents across both urban and rural regions. While many BCAs suggested that this was widespread practice by accredited private organisations, and were quick to blame Kāinga Ora’s Consentium, other feedback suggests that this may be equally happening between BCAs by those who are able to offer greater pay for experienced BCOs.

This is leading some BCAs to consider how they sufficiently attract and retain competent staff, particularly in smaller regions where they often have fewer applicants for roles and limited funding for wages. The workload pressures that BCOs are facing through the consent system are seen as contributing to stress and job dissatisfaction, which may only be exacerbating the capacity constraints that they are experiencing.

Capacity constraints may be contributing to greater numbers of unnecessary RFIs

Workforce constraints may also be leading many in the sector to submit poor quality or incomplete work rather than putting in the effort up front to ensure it has the required information. Feedback from BCOs indicated that they often received applications that were incomplete or missing basic information.

BCOs felt that this behaviour meant that applicants could place the blame for processing delays on them to “save face” with their clients. However, this was seen as only prolonging the issue as it meant that the responsibility for remediation was shifted between BCAs and the sector.

“We understand there are time constraints laid out from the clients. But they need to understand that if they don't give us a compliant application, they're going to get RFIs and instead of saving time…they’re actually losing it.” – BCO

On the other hand, the sector felt that BCAs were managing their workloads to meet the statutory timeframes by issuing “day 19 RFIs” to stop the clock. BCOs suggested this was a misconception and that RFIs were typically issued earlier in the timeframe. Due to the lack of sufficient data on RFIs, this feedback is unable to be substantiated by quantitative evidence but may be worth exploring in subsequent research.

Low BCA capacity may be contributing to issues with booking inspections

A number of sector professionals noted that due to long wait times for booking inspections, it was challenging to estimate the completion time for their work and align the inspections appropriately. Some BCAs noted that inspections typically needed to be booked at least two weeks in advance due to the lack of available inspectors.

This often resulted in building work not being completed in time for inspections and resulted in failures purely on those grounds. BCA respondents agreed that this was an issue and noted that they would often turn up to building sites and find that the work to be inspected was not complete.

“We do fail a number of inspections but not all of them are true fails. It could be that when we go to inspect the foundations, the consent includes three slabs, and only one is complete so the inspection would fail. So when the stats come out that [the BCA] fails a certain percentage, maybe 50-60% of inspections, it’s not a true representation of the pass/fail rate.” – BCO

Aware that they are likely to fail at least one inspection on timing grounds, the sector approach is often to book several inspections at a time and later cancel those they don’t need, further straining the capacity of the system.

The sector is becoming increasingly specialised, leading to challenges with oversight

The sector is also becoming increasingly fragmented as individuals focus on areas of expertise in order to create efficiencies in their work.

However, feedback indicates that this increasing focus on specialisation has the effect of creating less efficiency across the broader sector, due to a lack of end-to-end expert oversight and greater risk of error between construction stages.

BCOs suggested that site supervisors often worked across multiple building sites and were not always available when they turned up for inspections. More than half of BCA survey respondents considered this to be a big issue.

A lack of supervision was also seen as contributing to BCOs having to take on greater roles in regard to quality assurance. BCOs said this was a particular frustration between the design and building phases of a building project, or between specialist building teams that might not be working on a building site at the same time. BCOs expressed concerns about errors that could have been avoided with better communication or coordination between teams, and felt that they were having to take on that role when they carried out inspections.

BCA workloads are often constrained by their range of consenting responsibilities

Nearly all BCOs spoke about the challenges with balancing their consenting function with their accreditation requirements, which are compulsory to ensure that they have the policies and procedures in place to effectively carry out their role.

Most BCOs expressed frustration over their BCA accreditation assessments becoming too process-focused, detailed and “nit-picky”. Instead, they felt it has become a “tick-box exercise” that does not look much into the quality of BCA decisions. Many pointed out that while the accreditation is intended to improve their processes, it is not kept at a high level, assuring that the processes they have in place contribute to good decision-making. Many said training their staff and preparing for the assessments takes significant time and resources when they could be carrying out their consenting work.

“The time cost and energy for each audit is crippling when these resources could be better used.” – BCO

In addition, a number of BCOs spoke about the complexity of managing building work that was exempt from requiring a building consent under Schedule 1 of the Building Act. While obtaining a building consent was not necessary for certain types of building work, it is still required to comply with the Building Code. Problems tended to arise if questions or complaints were raised by the public or members of the sector about building work that may not comply with the Building Code. BCOs said that they were obligated to investigate any such issues that were brought to their attention, which could take significant resource away from their everyday work.

4.2 There are concerns about poor capability across the system

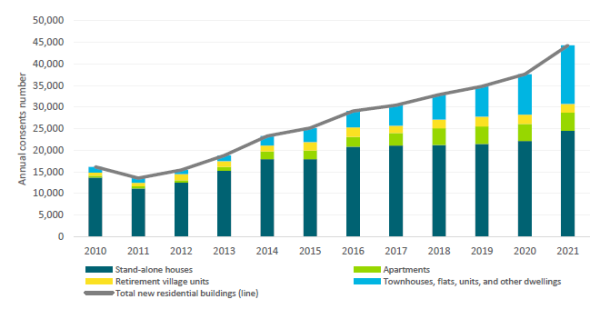

Alongside the increasing numbers of building consents being processed through the system, increasing densification and advancements in building technology has led to buildings becoming increasingly challenging to build and regulate. In the past decade, the proportion of stand-alone houses dropped from 82 per cent of all residential dwellings consented in 2011 to 55 per cent in 2021. The proportion of multi-unit homes, however, increased from 12 per cent to 40 per cent during the same time period (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Annual new residential dwellings consented by building type (year ended June 2010–2021)[12]

The building system has accordingly adapted its regulatory levers to reflect the changing nature of the industry and standards for building work by regularly reviewing the requirements of the Building Code and setting standards for people and products within the system. Under the Building (Accreditation of Building Consent Authorities) Regulations 2006, BCOs carrying out technical roles as part of their building control functions must have a technical qualification. Similarly, a 2007 amendment to the Building Act specified that those who carry out or supervise restricted design or building work must be assessed as being competent under the Licensed Building Practitioner Scheme or other recognised regimes that include licensed professionals such as Architects, Chartered Professional Engineers, or Plumbers, Gasfitters and Drainlayers.

However, the quality of work carried out during the building consent process was considered a key issue by both BCAs and sector professionals, with each group pointing to concerns about the skill and capability of the other. These concerns highlight potential gaps in capability that may be contributing to issues in the consent system.

The scope of required knowledge for BCOs is increasing

As the sector becomes increasingly complex and specialised, there are concerns that BCOs do not have the necessary expertise to adequately assess technical details across all aspects of design and building work.

Some survey participants pointed out that it is impossible for the BCAs to have all the necessary skills to do this effectively. Both BCA and sector respondents felt that this often leads to BCOs falling back on what they know or relying on rigid checklists, thus limiting uptake of more innovative building methods.

“As architects we are relying on alternative solutions, best practice and our knowledge to provide creative, interesting and healthy design solutions that benefit the built framework of this country. More often than not the person behind the desk is unable to engage with our approach, and rather refers back to the outdated NZBC E2 when an alternative solution is applicable.” – Architect

More than half of sector survey respondents said that a big issue for them was that “some BCAs lack the experience to understand more complex building projects“. Feedback from the sector suggests that while the BCOs may have sufficient regulatory knowledge, they may also be lacking the practical ability to interpret technical drawings and construction methods.

“Building consent officers often seem to have insufficient knowledge of construction and their ability to read and understand technical drawings is inadequate, resulting in too many basic and unnecessary questions.” – Architect

BCA interviewees suggested that while larger BCAs had the capacity to retain experts from a range of fields, smaller BCAs often had fewer BCOs and fewer resources to contract advice from external professionals. In addition, smaller BCAs typically receive fewer applications for more complex building types such as higher density housing or commercial buildings, so felt that they were not able to gain the same confidence and experience in working with these types of buildings through their everyday work.

There is concern that the sector is not keeping up with changes in building standards

A number of interviewees from both sides raised issues around inexperienced architects, engineers, builders and project managers undertaking work above their skill level and experience. The survey results showed that from a BCA perspective, some sector professionals lacked the skills to adequately understand the Building Code. The majority of BCA respondents (82 per cent) said this was a big issue. BCAs commented that many in the sector seemed to be unfamiliar with the requirements of consenting processes and often submitted incomplete documentation in their application. These issues often lead to multiple RFIs, lengthy delays, rework and inspectors having to educate inexperienced builders and project managers on site.

“The NZ building industry has become too focused on process…rather than developing a competent sector capable of understanding modern construction practices for new buildings and renovation of existing buildings.” – BCO

BCOs and sector professionals largely agreed that there needs to be more industry training focused on the Building Code and engaging with regulatory system. Some sector professionals said their degree focused more on theories and principles and there is not much in the curriculum around the regulatory system, the broader context of the build and other practical matters.

BCOs have the view that sector needs to do their part of understanding the Building Code and being proactive in keeping up with legislation, instead of just waiting to receive RFIs. BCOs felt that many RFIs may be caused by applicants’ not keeping up with changes in regulations, and not reading guidelines and information provided by BCAs and MBIE. On the other hand, the sector felt that updates to regulations were often rolled out with very little promotion or communicated in ways that they were not always aware of.

“Often we don’t realise there are changes to standards that we have been used to working with for a long period of time.” – Builder

Poor performance is seen as being shifted through the process rather than effectively managed by the sector

There was a strong theme in the feedback from BCOs that they lacked confidence that the sector was effectively managing the performance of those working within the building industry. While there were some concerns about the standards for those entering the building workforce, such as the requirements for entering the LBP scheme, the BCOs were more often concerned about mechanisms for dealing with poor quality work they saw in consent applications and building work inspections. This had implications on the ability of BCOs to carry out their work efficiently and to feel confident in the decisions they were making about the quality of building work.

BCOs spoke about sending out numerous, often repetitive, RFIs to applicants who appeared to have little understanding of the requirements of the consenting process. On building sites, BCOs noted that it was often easier to provide advice on how to address issues (despite this advice being outside the scope of their role) rather than deal with repeated failed inspections, which would only increase their workload. Poor building work was frequently attributed to supervisors being spread too thinly across building sites and not providing appropriate levels of oversight for their workers.

Particularly in smaller regions, BCOs said they were able to recognise those who were habitually poor performers but felt they had insufficient recourse for weeding out bad actors. While BCAs are able to charge hourly fees for application reviews or site inspections, they suggested that these costs are often being passed along to clients and are not seen to be enough of a disincentive for people carrying out substandard work.

“The council provides a sort of indirect incentive in that they charge by the hour. So if someone puts in a good quality application, the client is going to get a lower cost. Due to the way that clients usually often pay a fixed fee to the designer, in theory the designer could pocket any difference in fees that come from submitting a higher quality application that takes less time to process. If the designer is just passing on the charge then that incentive is not there.” – BCO

BCOs commented that official complaints mechanisms were difficult and time consuming to access on top of already existing capacity constraints. In addition, they spoke about the seemingly minor repercussions faced by the subjects of complaints, many of whom were still able to carry out building work in some capacity.

“The LBP scheme…everybody's just so cynical about it. BCAs are nervous about some designers but when they put a complaint, the complaint falls on onto the floor, and it’s like, ‘move on nothing to see here’. And [the designers] just continue to practice and repeat the same mistakes.” – BCO

4.3 There are concerns about the way in which people are carrying out their roles in the system

The consent system relies on having people with the capacity and competency to undertake their roles appropriately. However, there are concerns from both BCAs and the sector that people are not always carrying out their roles and responsibilities in a way that encourages efficiency, predictability and effectiveness in the system.

BCAs face tension between carrying out their role and providing good service

BCAs frequently commented that the standard of applications they received was poor, with many applications missing critical information required to begin the review process, such as names and dates. This is supported by the assessment carried out by IANZ, which found that “BCAs frequently accept building consent applications that do not have the necessary information to start processing the building consent effectively”, noting that they should not be accepting such applications.[13]

Many BCOs noted that this acceptance of incomplete and poor-quality applications was because they faced pressure as members of a public organisation to provide good customer service and felt unable to reject applications outright. However, this issue was then typically resolved by issuing RFIs for the missing information, thereby prolonging the application process.

Some frustrations also stemmed from how individual councils managed relationships and communication with the sector. Some BCOs felt that their BCA took a more customer-centric approach and were willing to help designers and builders by providing advice. However, many BCOs said that they did not have the capacity to do this, as it required additional time and was outside the scope of their role.

Many in the sector appear to be relying on BCAs to carry out quality assurance

BCOs often talked about taking a cautious approach when reviewing consent applications to ensure that the threshold for “reasonable grounds” was satisfied with a high degree of certainty. This appears to be contributing to sector professionals seeing RFIs as an inevitability when submitting their work and may then be reinforcing the use of BCAs to check for errors, as it creates disincentives to putting in the necessary work to “get it right the first time”.

“A lot of designers put applications in just for shopping, relying on BCAs to pick errors up, rather than going an extra mile and making sure they don't get the RFIs.” – BCO

BCA respondents often described the significant challenges they face in reviewing incomplete or inadequate building consent applications, suggesting that many applicants appear to be expecting the BCAs to review the applications for both completeness and quality. The result of this is that BCAs are spending more time reviewing applications and often sending out RFIs to resolve concerns with the documentation. Almost all BCA survey respondents (96 per cent) identified this practice as a ‘big issue’ for how they undertake their role in the building consent system.

“We get the blame for the delays but we are purely reactionary. We only react to what was provided to us and what’s on site for us to look at. We are just doing our jobs to ensure buildings are safe, healthy and durable.” – BCO

At the same time, sector professionals generally felt that BCAs would be overly cautious when carrying out their consenting function, finding faults regardless of the quality of work the sector produces. This assumption may then be discouraging the sector from carrying out their own quality assurance, as they believe that BCAs will review their work and point out any issues to resolve.

These attitudes therefore appear to be creating negatively reinforcing behaviours when it comes to quality assurance processes: as BCOs take what is seen as an overly cautious approach to decision-making, members of the sector may be disincentivised to take responsibility for their own quality assurance. This may be contributing to a culture of finger-pointing, as both sides blame each other for poor quality work and delays in the system.

There is low trust between BCAs and the sector

A strong theme from both BCA and sector respondents was that BCAs had a lack of confidence or trust in sector capability, leading to BCAs taking on additional responsibilities. This was cited primarily as having an impact on the efficiency of the consent system, through large numbers of RFIs, or BCOs re-checking work already signed off by sector professionals.

“Inconsistency from plan checkers and a very risk averse nature results in overly arduous RFIs. Often asked for more info when there are producer statements and engineers covering these areas of work.” – Builder

Sector professionals, both interview and survey respondents, expressed frustration that their experience and expertise weren’t being recognised by BCOs. A common complaint was that BCOs are double-checking the work already signed off by specialists, resulting in unnecessary delays. Survey respondents commented that because of a small number of poor performers in the sector, BCAs were taking an overly cautious approach to all applications, resulting in little incentive for those in the sector to strive to be a high performer.

At the same time, sector professionals often questioned the cause of delays in the processing of consent applications, seeing them as indicators of BCA ineffectiveness.

“The biggest issue is generally the incompetence of the council personnel performing the consent process. A knowledgeable person should be able to review a basic house plan in 2 days.” – Builder

Sector professionals suggested that for more complex builds, BCAs tend to issue “excessive” or “unnecessary” RFIs in order to use the “stop the clock” mechanism. This stops the time on the 20-working day processing deadline and is seen as giving BCAs more time to assess the application or contract an expert who could review the design on their behalf.

Sector professionals consider that overly risk-averse behaviour from BCAs is leading to inefficiencies in the consent process

The process settings, whereby the BCAs ultimately make decisions on reasonable grounds in relation to compliance with the Building Code, place considerable responsibility for providing assurance for building work onto BCAs. This leads to behaviours in BCAs that are widely considered to be “excessively” risk-averse by those in the sector.

Many in the sector complained that BCOs take an overly cautious approach to carrying out their consenting duties by issuing “nit-picky” RFIs and duplicating effort already carried out by sector professionals. Sector respondents suggested that this behaviour was largely driven by BCA concerns about accountability, with around three-quarters of sector survey respondents agreeing that “overly risk-averse behaviours from BCAs” was a big issue for them.

“BCAs are overly risk averse. …and results in excessive delay in processing and excessive number of irrelevant RFIs because BCA staff are unwilling or unauthorised to process consents decisively and confidently.” – Architect

“The Territorial Authorities are completely devoid of any awareness of the cost they inflict due to their overzealous risk liability aversion.” – Designer

On the other hand, BCOs justified this behaviour and said that because they were the ones who held specific responsibilities both as officials and for most, as local councils, they needed to create sufficient certainties that design and building work would not create negative impacts for themselves or building users, for whom they felt responsible.

“As a council, our role is to make sure that people can use buildings safely and if anything happens, that they can get out safely. You want to be confident that if you give someone a CCC that it’s built to Code, that it’s safe to use and that it’s going to last. Without BCAs carrying out that regulatory function, you are going to get people who will try and cut corners, so our role is critical to making sure that building work is carried out properly.” – BCO

However, many BCOs noted that “reasonable grounds” is subjective by nature and there is no clear definition of how it should be interpreted. This leads to differences in the level of rigour applied to applications and inspections based on a BCA’s appetite for risk, which in turn results in unpredictable outcomes of decision-making.

“Having the same checklists and systems across the country might help to some extent but if the liability still sits with the individual council then each one will continue to look at things differently.” – BCO

Many BCOs said that they felt this decision came down to personal opinion of what was considered “reasonable”. They also suggested that this uncertainty contributed to higher numbers of what could be considered “pedantic” RFIs as BCOs sought assurances that they had sufficiently covered off what could be considered “reasonable grounds”. These higher numbers of RFIs then contribute to delays in processing as applications are put on hold while awaiting responses.

“Our biggest challenge is that ‘reasonable grounds’ is never defined… The Code is just so flexible with its meaning for ‘reasonable grounds’ that anyone can literally do anything with it.” – BCO

4.4 Process-related complaints are contributing to frustration

In addition to the main issues that centred around the capacity, capability and behaviour of those who interact with the building consent process, there were also some general concerns about the process. These concerns often did not contribute to specific issues related to the efficiency, predictability or effectiveness of the building consent system but were frustrations shared by many across BCAs and the building sector.

The statutory 20-day processing timeframe is causing confusion and uncertainty

The processing time for a consent application starts when the BCA has accepted the application, usually after a check for completeness. Often this is within 48 hours of receiving the application, based on guidance from MBIE. The clock is stopped if the BCA requires additional information to properly assess the application and starts again when the response is accepted from the applicant.

With the majority of applications now submitted online, the general expectation from applicants is that the time starts once they have submitted the application to the BCA, leading to a disconnect in regard to when the clock actually starts. BCOs said this was a particular issue when applicants submitted their documents on a Friday afternoon or before the Christmas holiday period, with many applicants expecting the clock to start immediately.

The available evidence suggests that most consent applications are processed in the 20-day timeframe; however, with many applications going on hold pending further information, the actual processing timeframe is often much longer. This is contributing to considerable frustration from the sector due to the uncertainty and being unable to plan their work accordingly.

“It is supposed to be 20 working days and we are consistently seeing consents not being issued until 45+ days.” – Builder

Variability in IT systems across BCAs is contributing to administrative inefficiencies

A review of BCA processes and IT systems found that differences between BCAs can result in different expectations about what information is included and how it is organised in an application. Sector professionals who work across BCAs reported frustration that there was no standard process or system for submitting applications, leading to increased time required to adapt to different procedures.

Thirty-six per cent of both sector and BCA survey respondents felt that inconsistency of IT systems between BCAs was a ‘big issue’. Many respondents to the sector survey asked why there couldn’t be a single portal for submitting applications with some noting that it would save considerable time if they were able to have a standard template able to be submitted across BCAs.

“The different software systems are painful, particularly in regions where we work in two cities that run with two different systems” – Builder

In early 2021, a survey was carried out to identify IT platforms currently being used by BCAs to manage applications, inspections, and issuing of code compliance certificates. This research identified more than a dozen platforms currently in use and found that few if any of these were end-to-end solutions. On average, BCAs were using 2.4 different platforms to manage the building consent process.

While the use of different systems was typically raised by sector respondents, some BCA interview respondents noted that procuring and maintaining these IT systems can represent a significant cost burden to smaller BCAs. There were some views that having greater consistency of IT systems across regions would have the potential to create efficiencies in terms of cost and information sharing for those BCAs.

Some BCAs have been undertaking trials of remote inspection processes where the inspection is carried out by video. This has been seen as an opportunity to create greater efficiency in this process but there are still concerns about the limitations of this technology and the level of risk it introduces by not having an on-site inspector.

The volume of documentation included in consent applications is increasing

Both BCA and sector respondents reported that the increasing volume of material presented in building consent applications is a significant issue. The volume of information in applications was identified as negatively impacting the efficiency of the building consent process, slowing down both the preparation and assessment of applications, and resulting in potentially avoidable RFIs.

Interestingly, the increasing volume of material presented in building consent applications was identified as an issue by both BCAs and sector respondents; however, each group of respondents appear to believe the other is the cause of this issue. BCAs noted that applications are being submitted with “excessive” or irrelevant details included, making it difficult to find necessary information and contributing to RFIs. The sector noted that BCA documentation requirements have increased considerably, particularly around materials, increasing the time it takes to prepare applications.

“Architects are having to supply incredible amounts of info with BC applications … We are supplying full GIB manuals (for example) with every BC application as the BCA requests.” – Architect

Evidence indicates that unnecessary information included in applications is a widespread issue, affecting the efficiency of the building consent system. This issue was identified across regions, during both interviews and focus group discussions. BCA respondents described applications for relatively simple building work that were over 1,000 pages in length. A recent review of Kāinga Ora building consents found that applications for stand-alone houses could range anywhere from 700 pages to around 1,600 pages, and often included hundreds of pages of “unnecessary” information.[14]

Survey respondents were asked whether this was an issue affecting their role in the building consent system. Around one-third of BCA respondents (36 per cent) reported this was a big issue, and a further 54 per cent noted it was a small issue. This appears to be a more pressing issue for sector respondents, 55 per cent of whom reported that this was a big issue, and a further 29 per cent noting it was a small issue.

Alternatives to Acceptable Solutions are considered too difficult to implement

Architects and developers commented about unclear and inconsistent pathways for alternative solutions to become accepted as meeting Building Code requirements. There is an obligation on the applicants to demonstrate how their solution complies with the Building Code. However, interviewees noted that there is no guarantee that BCAs will accept these solutions, despite providing what they consider to be costly and onerous documentation.

“The Compliance Documents are not mandatory solutions, but BCAs seem totally incapable of considering or accepting any solution that does not exactly match Compliance Document solutions. So we do not have the performance-based system that the Building Act envisaged.” – Architect

A 2017 review of Auckland Council processes found that they were less likely to approve products and systems that were not recognised in the Building Code and that “Acceptable Solutions can become the only acceptable solutions, unless proven otherwise”.[15]

As a result, the current system appears to be discouraging innovation, leading to design and building work that is more likely to meet only the minimum standards outlined in the Building Code. The extent to which this is an issue is currently unknown and may be better understood with improved data on building consents and outcomes.

Footnotes

[10] Stats NZ, Building Consents Issued.

[11] Stats NZ, Household Labour Force Survey.

[12] Stats NZ, Building Consents Issued.

[13] International Accreditation New Zealand, 2021.

[14] Independent Expert Panel commissioned by MBIE, 2021.

[15] Auckland Mayoral Housing Taskforce, 2017.