2. Evaluation background and purpose

The current building consent system was established by the Building Act 1991 and has since been strengthened under the Building Act 2004. It functions as a critical component of the building regulatory system to ensure that building work is designed and carried out according to the Building Code.

On this page I tēnei whārangi

However, the system is frequently criticised for being inefficient, difficult to understand and unpredictable, adding additional costs and delays to building projects. This evaluation was commissioned by the Building System Performance branch in MBIE to better understand how well the current system is aligned with its intended objectives and to explore the underlying causes of issues with its efficiency, predictability and effectiveness.

2.1 The building consent system

The building consent system comprises the people, processes and regulatory environment that together provide assurance that building design and construction work complies with the requirements of the New Zealand Building Code.

Responsibilities are shared by a number of people in the building system

The Building Act 2004 sets out the following roles and responsibilities for the people working within the building consent system:

- Building owners are responsible for obtaining any necessary building consents, arranging inspections and applying for code compliance certificates after all building work has been completed.

- Builders are responsible for ensuring that building work complies with the building consent and the plans, or if a building consent is not required, the Building Code.

- Designers are responsible for ensuring that the plans, specifications or advice for building work are sufficient to result in the building work complying with the Building Code, if the building work were properly completed in accordance with those plans, specifications or advice. However, designers do not have specific accountabilities to ensure that their work complies with the Building Code, unless the design relates to restricted building work under the Licensed Building Practitioners Scheme.

- Building Consent Authorities (BCAs) are responsible for checking to ensure that an application for a building consent complies with the Building Code and that building work has been carried out in accordance with the building consent for that work. They are also responsible for issuing building consents and code compliance certificates.

- The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) is the agency responsible for the Building Act 2004 and associated regulations. MBIE’s role as steward and central regulator includes setting standards and monitoring performance, as well as providing system leadership and oversight.

All 67 territorial authorities (except the Chatham Islands[1]) act as BCAs for their district. Other entities may be registered by MBIE to perform the functions of a BCA and are commonly referred to as private BCAs. Consentium, an independent division of Kāinga Ora, is currently the only private BCA. A few other privately run firms also contract their services to territorial authority BCAs but are not registered as private BCAs.

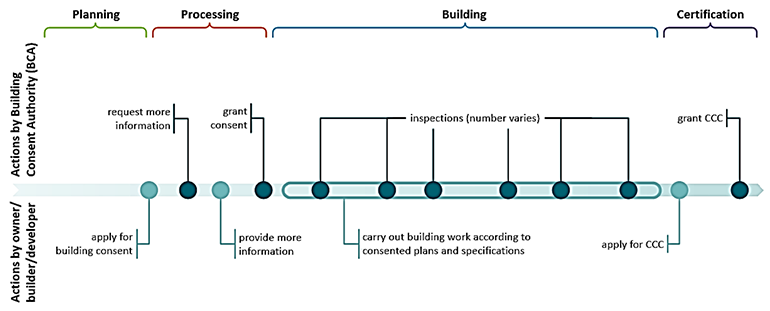

The consent system includes the steps to ensure compliance with the Building Code

The ‘building consent process’ refers to the series of steps by which a building project is reviewed before, during and after construction to provide assurance that it meets the performance standards of the New Zealand Building Code. It includes the entire process of checking plans, carrying out inspections and issuing code compliance certificates once building work has been completed. The process helps manage the risks of non-compliant building work.

The building consent process can be split into four distinct stages:

- planning and lodging the application

- processing the building consent application

- inspecting the building work

- issuing the code compliance certificate.

The key responsibilities within each of these stages are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1 : Overview of responsibilities across key stages of the building consent process[2]

Text of Figure 1.

A good regulatory system should be efficient, consistent and effective

Like all good regulatory systems, the building consent system needs to operate efficiently, consistently and effectively. This means that the system must be able to deliver on its intended outcomes in a way that is fair and predictable, while minimising undue costs and burdens.[3]

A workshop was held with key MBIE and local government stakeholders to better understand the concepts of efficiency, predictability and effectiveness in relation to the building consent system. The aim was to ensure a shared understanding of these terms to guide the evaluation.

The workshop participants agreed that these terms are difficult to succinctly define. However, there was broad agreement that:

- An efficient system maximises outputs with minimum inputs. In the context of the building consent system this would be evident in reduced double handling, faster flows of applications and inspections through the process, and builds being completed on schedule. Stakeholders at the workshop agreed that a key factor in ensuring efficiency of the building consent process is an appropriate assessment of risk, taking into account the complexity of the build.

- A predictable system provides users with the confidence that the process will get things right. Although variations might exist with how consents are processed by different BCAs, there should be a high degree of consistency in the interpretation of the Building Code and ‘reasonable grounds’ when assessing applications. In the context of the building consent process, this would be evident in similar applications having comparable outcomes across different BCAs.

- An effective system does what it is designed to do. This results in increased trust and confidence between all players (BCAs, builders, designers, owners, etc.). In the context of the building consent system this would be evident in fewer failed inspections, and assurance that buildings are safe and durable.

2.2 The purpose of this evaluation

The purpose of this evaluation was to understand how well the current system is aligned with its intent to ensure the delivery of safe, durable and healthy buildings. It also aimed to better understand the issues arising in the building consent system that are contributing to problems with its efficiency, predictability and effectiveness in operation, and to explore their underlying causes.

This information will be used to support further consultation and a review of the building consent system being undertaken by MBIE.

Findings in this report integrate the analysis of a wide range of information sources

This evaluation used a variety of methods to collect data before bringing this data together during analysis. This triangulation of data sources can help provide assurance that the findings are robust if multiple data sources are supporting the same finding. This approach can also help identify areas where there are conflicting views.

The methods used in this evaluation include:

- 43 interviews with 59 individuals from BCAs and the construction sector

- 5 focus groups bringing together 41 representatives from BCAs and the sector

- surveys that achieved 28 responses from BCAs and 263 responses from the sector[4]

- a comparison of the steps taken by BCAs when carrying out the consenting process

- visits to building sites, engaging with one or more building system stakeholders on-site

- a review of previous research related to the building consent system (see Appendix A for a list of relevant resources).

The evaluation team drew together information sources in their analysis, collectively agreeing on key themes. Following this, the evaluation team facilitated two workshops with a broad range of policy colleagues. The workshops provided an opportunity to test out initial findings and draw on the extensive knowledge of the building system across MBIE.

This evaluation focused on the people and processes in the building consent system

The evaluation was designed to explore the building consent process and the way that people carry out their roles through the process. It sought to understand the underlying issues contributing to problems with the process. It does not seek to identify or measure the impact of these causes on the outcomes of the building consent system.

This evaluation does not specifically look at the use of building products and how they are considered throughout the building process, nor does it look in detail at regulations that support the building consent system, such as the Building Consent Authority Accreditation Scheme and the Licensed Building Practitioner Scheme. However, these factors may be addressed in cases where they are seen to have an impact on the way that the building consent process is carried out.

Some information gaps remain and may be explored in future research

Quantitative data about building consent activity is mostly limited to the number, floor area and value of consents for building work. Official statistics also understate the number of consents processed by BCAs as they do not include low-value consents. Where information is collected about the processing of applications (including requests for information), inspection of building work and issuing of certificates of code compliance, this is held by individual BCAs and may not be collected in a way that is comparable across regions.

In addition, the relatively tight timeframes for the evaluation fieldwork meant that in-depth research across all regions and participants in the building consent system was not an option. Further considerations were given to various COVID-19 alert levels, and the unprecedented level of activity in the building consent system at the time fieldwork was being undertaken.

Despite these limitations, the evaluation provided evidence that substantiates anecdotal issues previously raised by stakeholders about the building consent system. It also points to areas for further in-depth research.

Details about the evaluation approach and methodology can be found in Appendix B.

Footnotes

[1] The Chatham Islands Council transferred its building consenting functions to Wellington City Council.

[2] MBIE Briefing 2021-1566: Developing a new system for building consenting. 4 March 2021.

[3] The Treasury, 2017.

[4] The response rate for the sector survey was very low, and as a result, sector survey findings should be considered broadly indicative of trends rather than statistically accurate measurements.