Annex 1: Summary of review findings and stakeholder engagement themes

On this page

Review methodology

4 streams of analysis were undertaken to understand the case for change and to support the development of options:

Stream 1: Building out the context

A review of recent literature[30] on government investment in the screen sector was undertaken, with a focus on the different types of incentives offered internationally. This analysis considered the context for screen sector incentives, including why they were introduced, what they are meant to achieve and level of success, and the different incentive types and structures.

Stream 2: Future trends analysis

Consideration was given to likely and potential future trends for the screen sector and what the implications might be for New Zealand. Analysis included what these trends might mean for the New Zealand screen sector and identification of future opportunities and problems that could be addressed through existing or new policy settings.

Stream 3: Review of the current funding landscape

A review of the current funding available for productions, the strengths and weaknesses of the current approach and the key issues and opportunities. This analysis covered the New Zealand Screen Production Grant and other funding administered by the New Zealand Film Commission, NZonAir and Te Māngai Pāho.

Stream 4: Competitor analysis

A review of the current funding available for productions, the strengths and weaknesses of the current approach and the key issues and opportunities. This analysis covered the New Zealand Screen Production Grant and other funding administered by the New Zealand Film Commission, NZonAir and Te Māngai Pāho.

Findings

International literature review

Screen incentives are common internationally. These incentives are becoming increasingly generous to entice international business.

Few academic studies have generated clear evidence about the economic impacts of screen incentives through direct measurement and analysis of data. Many publications discuss the cultural value of screen content at a theoretical level, but few use quantitative or qualitative research methods to define and assess cultural benefits and how they are generated and distributed. The literature highlights the difficulty of measuring effects of screen incentives across different outcomes. Researchers suggest more tools for monitoring and evaluation would be useful to better understand the impact incentives have in cultural as well as economic terms.

Studies commissioned by entities responsible for funding or administering incentive programmes tend to focus on the economic impacts of incentive schemes. Benefits are broken down into direct, indirect and induced impacts.[31] Methods used generally include input-output models, with Gross Value Added as the main economic measure. The review demonstrates that commissioned studies tend not to examine counterfactuals or fiscal sustainability, or estimate opportunity costs, or costs associated with outcomes attributed to incentives, such as the cost per job created.[32] Generally, commissioned studies have a much stronger emphasis on the benefits generated by stimulating screen industry activity through incentives, while academic studies tend also to model the costs of such investments.

In New Zealand, 3 recent commissioned reports have estimated the impact of the screen sector on the New Zealand economy:

- A New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) report in 2017 assessed that the screen industry added $1.015b to GDP in 2016, and highlighted that the screen sector provides highly productive employment for New Zealand’s workforce. The report found that the typical postproduction/visual effects worker earns a median hourly rate of $65 compared to the national median for all industries at $23 per hour.[33]

- In March 2018 a report by the Sapere Research Group put the indicative net economic benefit of the screen sector at $361.1m. The report identified tourism benefits, export earnings, and the attraction of international students as key ways the screen sector contributes to the New Zealand economy. The application of screen sector knowledge, technology and assets to other high-tech industries is another key contribution.

- A 2022 report by Olsberg SPI added support to the assessment of the screen sector as valuable for the New Zealand economy, indicating that screen production has generated significant and increasing expenditure within New Zealand.[34]

Attracting international productions is important for supporting a domestic sector as international productions provide valuable opportunities for the domestic workforce in New Zealand, including highly paid positions, notable credits, and training and development opportunities.[35] However, this can have a dampening effect on domestic productions, as it has been observed internationally that in some cases the volume of service production overall may soar, but the volume of domestic production can decline, in part because labour and infrastructure resources are stretched.[36]

For those productions supported by the NZSPG, average earnings are as follows:[37]

NZSPG-New Zealand

| Film | TV | |

| Average earnings per job[38] | $13,552 | $17,665 |

| % of jobs done by NZ residents | 92.5% | 97.6% |

NZSPG-International

| Film | TV | |

| Average earnings per job[38] | $67,738 | $34,836 |

| % of jobs done by NZ residents | 81.7% | 90.9% |

Studies indicate that when choosing where to locate, large studios make decisions based on production budgets (including exchange rates, incentives and labour costs) and creative attachments (the actors, directors and producers). However, infrastructure and availability of local crew also play a key role in influencing decisions.

Much of the literature on screen incentives focuses on the film industry rather than on investment in the screen sector more broadly. This may be significant given the recent global trend towards much greater investment in the production of high-end television series versus feature films, as it could alter the cost/benefit ratio of incentives, particularly in relation to factors such as training and career development opportunities and consistency of work. There may be different benefits that flow from big productions (such as big-budget feature films) when compared with long productions (such as multi-season television productions).

Future trends

Research indicates that audience preferences for content and platforms are difficult to predict, but ease of access and the ability for individuals to curate their own diverse, high-quality screen content across all their devices will be important.

Technological change in the screen sector is constant. Major technological developments are transforming the screen production process, modes of consumption of content, and content itself. Screen-sector policy will need to change to accommodate these changes and any policy changes resulting from the review will need to provide certainty to support long-term industry planning and investment, as well as flexibility to enable industry to adapt to rapid ongoing change.

More content than ever is being produced[39], and it is available globally, across many different platforms rather than only traditional linear television or cinema release. The screen sector has seen rapid change in audience behaviour, enabled by technological change, and an increased digital convergence within the broader entertainment sector.

At the same time, finance available from traditional sources, such as advertising, is reducing. Broadcasters, online services, and film exhibitors are all competing for fracturing audience share and revenue. To combat fracturing audiences, content producers have shifted their focus towards global audiences. Overall, consumer spending on content is increasing significantly.[40]

Traditionally, film and TV shows are developed, financed, produced and promoted project by project. This means most workers are contracted to work on a specific production only for the duration of that production, impacting long-term career development and training. In NZ, 92.4% of workers – or 3,756 of 4,098 firms - were self-employed contractors in 2020.[41]

Virtually all job growth in New Zealand’s screen sector in the ten years to 2020 was in post-production, which has a focus on digital skills.[42] We expect demand for digital skills to continue to grow in the screen sector due to increasing consumer expectations for digital effects and new technologies to be used in productions.

The current funding landscape

A number of different business models underpin the screen sector internationally:

- Studio-financed productions,

- where the screen content is financed, developed, produced and distributed by the studio. As a result, control over the film production and IP resides with the studio, distributors and promoters. Large production studios often use this model.

- Content development outsourced to an independent producer. The producer is paid a fixed fee for their film, covering the creative development, production to final release. The fixed fee includes ownership of the IP for a certain length of time. Streaming platforms often use this model.

- Independent productions where producers/writers develop a concept and take it through to final production and release. Financing is sourced from a range of avenues, including private investors, banks, governments, distributors and promoters. Stakeholders have indicated that under this model, producers give away their equity share or creative control in the production to attract financing to fund the production budget.

The New Zealand domestic screen sector is part of this global production system and productions often use the independent production model to raise financing, including as official co-productions to access government support across a range of jurisdictions or to unlock broadcasting funding in other jurisdictions.

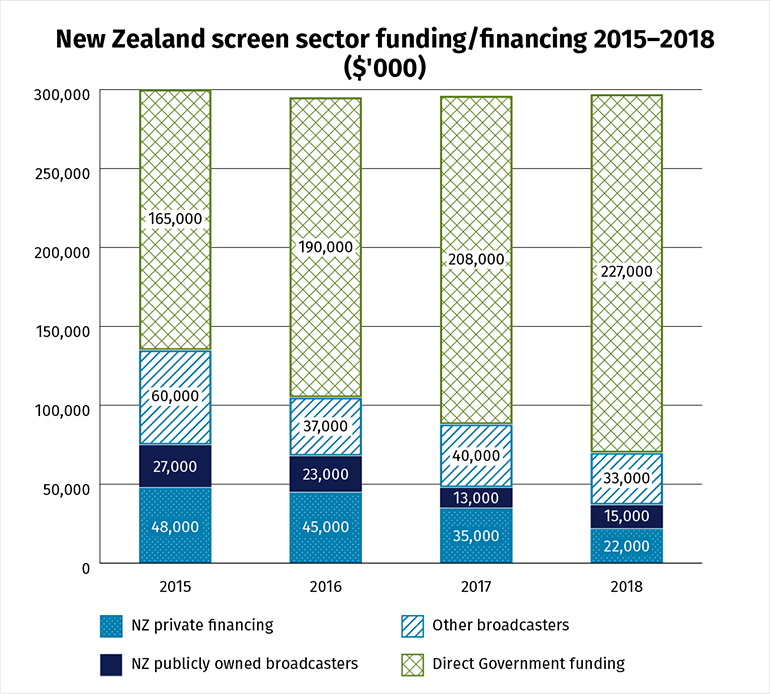

Since the introduction of the NZSPG, direct government investment to the screen sector has increased year-on-year, but overall financing has remained the same, as is demonstrated in Figure 5 below. This is notable given that the increase has occurred at the same time as an increase of consumer spending on film and TV internationally.

Figure 5: New Zealand screen sector funding/ financing 2015-2018 ($ millions)

Descriptive text of Figure 5

A review of existing government funding indicates that funds are overwhelmingly directed towards the production of content, rather than other screen industry activities such as development, promotion and distribution. Public funding has steadily increased as a proportion of overall funding for domestic productions since 2015. This indicates an increasing reliance on public funding by domestic productions, but we do not have a good understanding of why private funding has reduced.

The current government funding landscape for the New Zealand screen sector is complex and uncoordinated, making it difficult and inefficient to navigate. Monitoring and evaluation is lacking.

International landscape (competitor analysis)

As of 2022, there are over 100 active screen incentives across the world. Incentive headline rates are generally around 25%-35% of eligible expenditure and play a decisive role in where productions are sited. While the headline rate supports location decision making, other aspects are also important such as the definition of qualifying expenditure, economic and cultural tests and eligible formats and genres.

New Zealand’s screen sector is shaped by a number of characteristics that make ensuring our incentive settings are competitive particularly important. New Zealand is a small market, and we are a long way from key screen production markets. We also have a comparatively shallow labour pool and screen-specific infrastructure.

Stakeholders report that while New Zealand is considered a strong production location, our distance from Los Angeles is one of the main factors given for productions choosing not to locate here. Our comparative advantage appears to be a favourable exchange rate and the relatively low cost and conditions of labour. Australia, being equal distance from markets with similar exchange rate and purchasing power parity, is New Zealand’s closest competitor.

Comparison of international production incentives between New Zealand and other jurisdictions

Scheme name and incentive rate

New Zealand:

NZSPG-International (direct payment) 20%

PDV: 20% <$25m and 18% for >$25m

Australia:

Location Offset (tax credit) 16.5%

Location Incentive (direct payment) up to 13.5% of qualifying expenditure

PDV Offset (tax credit) 30%

Canada:

Production Services Tax Credit 16%

Ireland:

Section 481 Film Tax Credit 32% to 35% depending on meeting certain criteria

United Kingdom:

Creative Sector Tax Reliefs (tax credit) up to 25% on 80% of total core costs

Can additional screen incentives be accessed?

In New Zealand, productions may be invited for a 5% uplift

In Australia, both the Location Offset and Location Incentive can be stacked together if a production meets the criteria. A production may also seek additional state level incentives.

In Canada, productions can seek additional incentives from cities or provinces.

In Ireland, productions can seek a 5% regional uplift

In the United Kingdom, productions can seek regional uplifts

Scheme thresholds, fund or project caps, and expenditure definitions

In New Zealand, there is a minimum qualifying expenditure of $15m for films; $4m for other formats; $0.5m for PDV. There is no fund or project cap. Qualifying expenditure is defined as services and goods purchased by a production company in New Zealand. Overseas goods may qualify depending on meeting certain criteria.

In Australia, the Location Offset and Location Incentive have a minimum qualifying expenditure of A$15m for films, and an average of at least A$1m per hour (total QPE/duration of series measured in hours) for other formats. The PDV offset has a minimum qualifying expenditure of A$0.5m.

The Australian Location Offset and PDV Offset are uncapped, and the Location Incentive fund is capped up to A$540m FY 19/20 to 26/27. Qualifying expenditure for the Location Offset and Location Incentive is defined as Australian-based services and goods purchased by a production. For the PDV Offset, expenditure must have been incurred or attributable to goods and services provided in Australia.

In Canada, the Production Services Tax Credit requires minimum qualifying expenditure of CA$1m for single episodes less than 30mins, CA$0.2m for anything longer. There is no fund or project cap and only Canadian labour expenditure is eligible for the tax credit.

In Ireland, there is a minimum qualifying expenditure of EUR€0.25m for all formats. Project funding is capped at 80% of total production costs, or €70m, whichever is lower. Services and goods used in the production are eligible for the tax credit.

In the United Kingdom, a minimum of 10% of the core expenditure must be UK expenditure to be eligible for the tax relief. Expenditure is defined as goods and services which are used or consumed in the United Kingdom. There is no fund or project cap.

Unique economic or cultural tests

In New Zealand, a production must pass a significant economic benefits test assessed by a panel to receive the 5% Uplift.

In Australia, productions must be receiving the Location Offset and state level incentive to be eligible for the Location Incentive. Incentives received must be assessed as efficient, effective, economical, and ethical use of public resources. Productions receiving the Location Incentive must also demonstrate how the production is supporting Australian jobs, trainings and skill development both screen sector and wider economy.

In Canada, no unique economic or cultural tests are applied to productions accessing the Production Services Tax Credit.

In Ireland, the Section 481 Film Tax Credit requires that the holding company of the production must have 100% shareholding by an Irish resident company. Eligible productions must also:

- submit a skills development plan

- pass the Section 481 Cultural Test (meeting three out of eight set criteria)

- pass an industry development test

In the United Kingdom, a production must be certified as ‘British’ to be eligible for the Creative Sector Tax Reliefs.

The NZSPG package

NZSPG-International

Since 2016, NZ has attracted 5 productions (18%) over $100m in production budget in size (all of these productions received the 5% Uplift – Meg, Mulan, Ghost in the Shell, Pete’s Dragon, Mortal Engines). But the majority of productions attracted to New Zealand are under $25m in production budget size.

| 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | Total | |

| Over $200m | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| $100m-$200m | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| $50-$99m | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| $25-$49m | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| $10-$24m | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| Under $10m | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Total | 6 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 28 |

18 of the 28 productions (approximately 64%) accessing the NZSPG-International for live production shoots were one-off productions i.e. did not return to New Zealand between 2016 and 2021.

The 5% Uplift incentive is attractive to international studios, but the application process is a significant barrier. 5 productions received the 5% Uplift between 2016 and 2021. By value, the Uplift totaled 68% of the live production NZSPG.

The rules-based administration of the NZSPG-International and the uncapped nature of funding are viewed as strengths by international studios. New Zealand’s 20% incentive headline rate plus 5% Uplift is highly competitive, illustrated by our ability to attract very large international productions (over $100m in production budget size) consistently since the NZSPG was introduced.

Since 2019/20, Australia, has offered significantly large productions (over $100m) up to a 30% headline rate through access to an additional location incentive grant. Australia’s application process for the additional grant offers greater certainty and timeliness around decision making than the NZSPG 5% Uplift.

The high level of uncertainty around the invitation process for the 5% Uplift and the lack of clarity around the outcomes that need to be achieved by productions is diminishing the competitive advantage of the Uplift.

NZSPG-PDV

In 2017, the NZSPG-PDV rate was reduced from 20% down to 18% for production spending over a $25m threshold. The change to the NZSPG-PDV settings was intended to rein in a significant area of NZSPG expenditure.

New Zealand attracts a significantly higher number of international productions for PDV activity than for location shoots, but the NZSPG-PDV appears to be becoming less competitive internationally, illustrated by a decrease in the number of applications since 2017. The NZSPG-PDV offers a rate of 18-20%, while Australia offers 30-35% for the same activity. Australia has experienced an increase in PDV activity since 2018.

Because of the digital, more mobile nature of PDV work, screen productions are able to shift their visual effect and post-production activity to countries offering the highest incentive rate and relevant available skills. Providing more support to PDV incentives or opening up the PDV incentive to more innovative screen technology activity and/or a wider set of businesses, may be required to retain New Zealand’s competitive advantage in PDV activity.

In 2018, a Sapere research paper identified the total economic benefit from the various types of screen activity undertaken in New Zealand. The data indicates that when contract labour is included, PDV activity far outperforms the other types of productions in terms of its economic benefits.

NZSPG-New Zealand

The NZSPG-NZ has low production expenditure caps by comparison to other countries. Arguably this is incentivising low production budgets, with a potential associated impact on the quality of production. This may be acting as a deterrent for New Zealand content being picked up by international broadcasters or platforms.

The NZSPG-NZ is underpinned by complex criteria and processes, undermining business certainty. It is significantly more complex to navigate than the NZSPG-Int. Interpretation is required of the criteria by the NZSPG panel, making decision making variable and opaque.

New Zealand has a generous headline incentive rate supporting cultural content and/or domestic productions. New Zealand’s cultural content test supports a wide range of format types, for example reality TV (which is generally excluded in other countries). There is an opportunity to consider what is meant by cultural benefits and their associated value and rebalance incentive rates and/or criteria in response.

Co-productions

Across the package of NZSPG-incentives, expenditure of domestic productions is growing the fastest. This is underpinned by steady growth of co-productions. Co-productions are a growth segment internationally. Official co-productions can be a useful tool to support New Zealand producers to access international financing and bigger budgets.

By comparison to other countries, New Zealand offers generous domestic incentive. Accordingly, official co-productions are able to access the same generous rates. The NZSPG broadly has limited exclusions, a generous expenditure definition and few requirements for cultural content.

Stakeholder engagement

Since the announcement of the review in December 2021 MBIE and MCH have met with a range of screen-sector stakeholder groups to discuss the review and the current state of government funding in the screen sector. These discussions have given us the opportunity to understand the different perspectives from across the sector. Stakeholder perspectives have informed the development of the options presented here.

Keystakeholder themes can be broken into four main themes: views from the domestic screen sector; views from the international screen sector: themes related to skills; and themes related to infrastructure. A summary of the four themes is included below.

International

- New Zealand is becoming less competitive. Other countries are increasing their incentives

- NZSPG-Int settings are easy to understand and provide international productions with a high level of certainty around funding e.g. rules based and uncomplicated

- The 5% uplift process is complicated and uncertain

- The 5% uplift is too hard for too little benefit

- A lack of certainty around the uplift reduces the likelihood a production will choose to film in New Zealand

- International productions are essential for supporting and growing the domestic side of the sector

- General perception that review = cutting funding. This has spooked the horses

- ‘New Zealand stories’ do not need to be New Zealand sorties. A writer or producer from New Zealand is enough

- Production is global and audiences are global.

Domestic

- International productions can inhibit the capacity of the domestic industry to produce local content because they make it difficult for domestic productions to source crew at affordable rates

- International productions are seen by some as a financial enabler to produce local content

- The NZSPG is too heavily weighted to international productions

- The Terms of Reference for the review is too narrow – it should be expanded out to include a review of the function of NZFC

- Perception that the Government values the domestic industry only in terms of its value as a service provider to international productions

- The current structure directs NZFC resources towards attracting international productions, not advocating for domestic ones

- The 5% uplift is an excellent additional mechanism but could be better utilized

- Need to re-prioritise New Zealand stories and storytelling

- The current design of the NZSPG for international sis well positioned in the global market

- Current incentives might not be creating the right behaviours

- Production is local and audiences are local

Skills

- Career development and continuity of work is an ongoing issue

- Skills shortages reduce the production pipeline. The reduced production pipeline results in skills shortages

- International productions should be required to do more to provide training and ongoing employment for local screen workers

- The funding mechanism should be industry wide and include skills

- Industry groups and the private sector have been working on solutions but there needs to be government support

- Ideally government support would include direct investment but placing more emphasis on skills through the 5% uplift would be an improvement

Infrastructure

- In order to improve the quality of the production pipeline in New Zealand there needs to be proactive capability-building investment in infrastructure growth

- New Zealand lacks significant world-class infrastructure, and this creates an immediate and critical limitation on the consistency, scale and volume of our production pipeline

- Industry groups and the private sector have been working on this but there needs to be government support

- Ideally this support would be direct investment but placing more emphasis on infrastructure through the 5% uplift would be an improvement

- Relies on an on-going supply of international productions to de-risk infrastructure investment and build studio capacity.

Footnotes

30. The review included academic studies, commissioned reports, and other literature on government incentives for the screen sector published in the last decade.

32. Olsberg SPI 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022

33. The economic conribution of the screen industry(external link) [PDF 1.3MB]

34. Economic impact of the New Zealand Aotearoa Screen Production Sector(external link) [PDF 1MB]

35. Olsberg SPI Report on the Economic Impact of the New Zealand Screen Production Sector(external link) — New Zealand Film Commission Sector

36. Olsberg SPI Report on the Economic Impact of the New Zealand Screen Production Sector(external link) — New Zealand Film Commission Sector

37. Sapere, “Evaluating the New Zealand Screen Production Grant(external link)”, March 2018, pages 36 and 38. This is for grants during the period from 1 April 2014 to 1 July 2017.

38. These figures are for each job on a production supported by the NZSPG during the period from 1 April 2014 to 1 July 2017

39. The international media and entertainment sector has experienced strong growth, with revenue predicated to approach US$3tn by 2026 off a base of US$2.5tn in 2022. Spending on film and TV has increased from US$189b in 2019 to US$220b in 2020.

40. After a boom year in video streaming, what comes next?(external link) — PwC

41. Business Demography Statistics 2020.

42. Economic Trends in the New Zealand Screen Sector [PDF, 1.6 MB]

<Next steps | Annex 2>