What are the high-level options?

On this page I tēnei whārangi

The regulatory options presented for feedback in this discussion document are based on the existing regulatory frameworks for minerals/resource development in New Zealand. The Government does not have a preferred option at this stage and is open to alternative approaches that can achieve the objectives outlined.

This document seeks feedback on 2 high-level options:

- Option 1: Include hydrogen in the definition of a mineral to regulate it as a mineral under the CMA. This would mean that where mineral rights are privately owned (or owned by iwi under a customary marine title), the owner would have control over its development. Where mineral rights are held by the Crown, the right to access the minerals would be allocated under the CMA. Other regulatory requirements (e.g. environmental resource consents) would apply in both circumstances.

- Option 2: Exclude hydrogen in the definition of a mineral under the CMA and regulate it as a non-mineral natural resource. This could mean that (by default) hydrogen is allocated, and its effects managed primarily through the RMA[1]. An alternative is that a new allocation regime could be developed outside the RMA. Excluding hydrogen in the definition of a mineral under the CMA would allow hydrogen to be developed with a wider focus than the purpose of the CMA (e.g. reducing New Zealand’s emissions and improving energy security and resilience).

Option 1: Include hydrogen in the definition of a mineral to regulate it as a mineral under the CMA

What is the likely impact of regulating natural and orange hydrogen as a mineral?

Regulating hydrogen as a mineral would mean ownership of it would be the same as any other non-statute minerals in the land, in that it could be Crown or privately owned. Any hydrogen found in the territorial sea and in the exclusive economic zone would be Crown-owned.

Regulating hydrogen as a mineral would require some amendments to the CMA and the associated regulations such as explicitly including natural and orange hydrogen in the definition of mineral under the CMA. This would provide certainty and clarity that the CMA applies to any Crown-owned hydrogen. Some of the key considerations and changes that would be needed are outlined below. The intention would be to allocate rights to the hydrogen that the Crown owns in a way that maximises the benefit to New Zealand.

Health, safety and environmental requirements under relevant legislation would continue to apply to the development of hydrogen regardless of whether or not hydrogen is treated as a mineral under the CMA.

Issues with hydrogen occurring across multiple land parcels

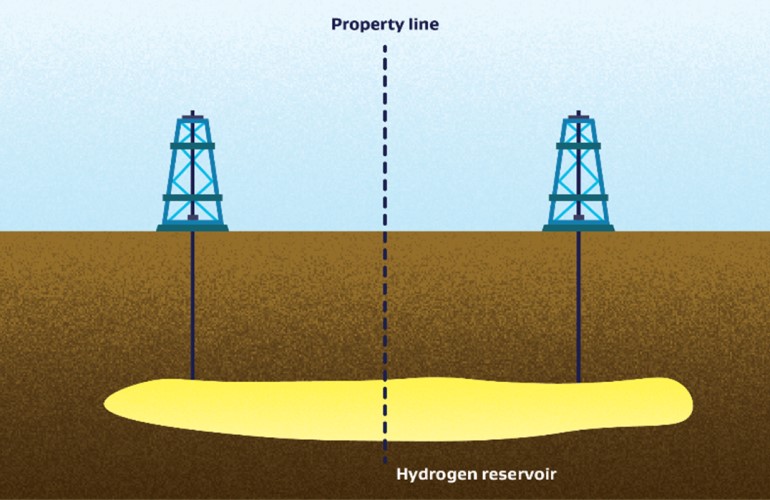

An underground reservoir containing natural hydrogen could cross land boundaries with different owners and therefore mineral rights. It could flow between Crown-owned and privately-owned land. In this case, tapping into one side of the reservoir means potentially extracting hydrogen from another property. This could lead to disputes around where the hydrogen is coming from and who owns it, making it difficult to develop. This is not an issue for petroleum (oil and gas) in New Zealand because it is nationalised and always Crown-owned.

In some overseas jurisdictions where petroleum is not nationalised, these issues are addressed using a mechanism called the “rule of capture”, which could be introduced within the CMA for natural hydrogen. Under this rule, a landowner has the right to extract and claim ownership of a resource that flows from a common reservoir beneath their land, even if that resource migrates from a neighbour’s property (as seen by the image below). All owners of a common hydrogen reservoir would have equal rights to develop the resource and therefore no one would have exclusive development rights.

A potential problem with the “rule of capture” is that it can encourage overproduction because ownership is shared over a common source. This could lead to damaging common hydrogen reservoirs. To prevent this, the rule of capture could have some limitations such as a duty on mineral rights owners to exercise the right to capture in a non-negligent and non-wasteful way (e.g. limiting the number of wells that could be drilled). The rule of capture could also be limited in other ways to ensure extraction is done fairly and equitably with the understanding that the resource is shared (e.g. production caps, well spacing and drilling requirements, unitisation[2]). Lessons can be taken from both international examples and domestic examples for similar resources, for example geothermal resources.

Which CMA requirements should apply?

There is a question as to which CMA requirements should apply to hydrogen if it is treated as mineral and whether new requirements are needed. Under the CMA, the requirements that apply to Crown-owned non-petroleum minerals are comparatively lighter touch with lower royalty requirements compared to the petroleum requirements (which cover volatile gases, higher royalty requirements, storage facilities, well drilling requirements, decommissioning and post-decommissioning obligations and financial security requirements).

Using petroleum requirements to regulate hydrogen is consistent with the emerging international approach, but all existing requirements in New Zealand may not be the most appropriate for an emerging industry with existing commercial uncertainty. For example, existing petroleum royalty rates, petroleum application fees and reporting requirements (which are designed for a mature industry) may not be conducive to incentivising development. Additionally, as petroleum is a nationalised resource in New Zealand, and petroleum requirements have been designed with this in mind, not all requirements may be fully transferable or appropriate for hydrogen. It may be more appropriate to assess and understand which petroleum requirements should be adapted and used for regulating hydrogen under the CMA (e.g. well drilling requirements) or if something new is required.

There are also some choices around how we can phase this work – we could try to address all requirements for the full life cycle for development now with the limited information we have about hydrogen development, or we could design detailed requirements once we learn more about the resource.

For example, we could focus our efforts on the requirements that should apply to prospecting and/or exploration permits for hydrogen to enable the industry to start, while taking further time to design what the later stages of development would look like (e.g. mining and decommissioning requirements).

How would this impact Māori rights or interests in hydrogen?

Regulating orange and natural hydrogen as a mineral would mean that the Crown would need to consult relevant iwi and hapū in allocating any rights to prospect, explore or mine Crown-owned hydrogen. Any of the Crown’s existing relationship agreements with iwi and hapū regarding Crown-owned minerals would automatically apply to hydrogen. In addition, the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 would provide the right for iwi, hapū and whānau ownership of hydrogen alongside other minerals within customary marine title areas.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of this option?

An advantage of this option is that it aligns with how most minerals are treated across New Zealand and enables the Crown to receive a fair financial return for its minerals for the benefit of New Zealand. It also means that the Crown would have a vested interest in hydrogen development, and would enable the Crown to collect valuable information about the resource which could enable its strategic development. Utilising relevant aspects of the existing regulatory framework may also have regulatory efficiencies as the requirements are well understood. The main disadvantage of this option is that ownership is mixed, based largely on property rights. This means that in some locations multiple permissions may be required, and for Crown-owned hydrogen, a CMA permit would be required on top of other consents and approvals (e.g. resource consents). This may incentivise the industry to avoid the CMA, and to extract privately-owned hydrogen where possible.

Option 2: Exclude hydrogen in the definition of a mineral under the CMA and regulate it as a non-mineral natural resource

What is the likely impact of regulating natural and orange hydrogen as a non-mineral natural resource?

Under this option the government would be clear that hydrogen was not a mineral under the CMA.

Regulating natural and orange hydrogen as a non-mineral natural resource would potentially allow for an allocation approach with a wider focus than the CMA. One reason to do this is to allow the regime to be less focused on royalties and more focused on a range of government priorities (like reducing New Zealand’s emissions and improving our energy resilience). It could allow for a regime where the Crown does not assert ownership of hydrogen but ensures it can be developed where appropriate.

Under this option, hydrogen would be regulated by default under existing environmental and health and safety regimes. Specifically, the RMA would be the central mechanism. Developers would need landowner consent to operate. This would include consent from Crown landowners such as the Department of Conservation if developing under Crown land. The developer would then need RMA consent to drill and develop the resource (including, for example, water take and discharge). The RMA consent could cover issues such as decommissioning of mining infrastructure or bonds if that was deemed necessary. With the requisite regulatory approvals and landowner agreement the developer could proceed to develop the resource.

Depending on the level of interest in developing natural and orange hydrogen in New Zealand, the regime could initially be a light touch approach where relevant consent authorities (e.g. regional councils) effectively allocate hydrogen through a first-in, first-served approach under the RMA. Like other resources, resource consent authorities would be responsible for managing allocation issues (e.g. hydrogen reservoir crossing land boundaries) through regional policy statements and plans. This could be similar to the approach taken with geothermal resources.

Amendments to the RMA may be required to enable this approach. The Government is currently progressing its resource management reforms and we would need to align with the reform process as it develops.

An alternative approach would be to develop a bespoke allocation and management regime for hydrogen outside the RMA, such as the Government is developing for offshore renewable energy, if the RMA is not considered suitable. We would need to consider the interaction of any bespoke legislation with the resource management regime. This is something that could be considered following the resource management reforms.

How would this impact Māori rights or interests in hydrogen?

Because hydrogen would sit outside of the CMA, the consultation and other Treaty-related provisions in the CMA would not apply. Treaty-related provision for resource consents under the RMA would still apply.

If a new legislative allocation regime is progressed outside of the resource management reforms, iwi involvement in the regime would need to be considered outside of the Crown minerals framework.

The Government is interested to understand iwi and hapū views on natural and orange hydrogen, including any rights or interests which may be relevant to its development.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of this option?

Compared with option 1, regulating hydrogen under the RMA would reduce the number of regulatory regimes a nascent industry would have to navigate. It would also enable consent authorities to develop regional plans to resolve issues around allocation as appropriate. A disadvantage of this option is that a first-in, first-served allocation approach is limited and may not be adequate for competing developers (but enabling different allocation methods is being considered as part of resource management reforms[3]). Another disadvantage is that regional councils may not have all the tools, funding, capacity, or specialist knowledge to manage hydrogen allocation under the RMA.

The alternative of developing bespoke legislation outside the RMA would ensure settings achieve the desired objectives but is likely to be costly, complex and resource and time intensive to implement compared to regulating under the CMA or RMA. The costs may outweigh benefits if hydrogen development is not commercially viable in New Zealand.

Questions for consultation

Hydrogen as a mineral under the CMA

2) Do you support regulating natural and orange hydrogen as a mineral?

3) What do you consider to be the advantages and disadvantages of this approach?

4) Do you see any unintended consequence or risks with the “rule of capture” and how it may work in practice? Please explain your answer and how these risks could be mitigated.

5) What CMA requirements should apply (e.g. non-petroleum mineral requirements, petroleum requirements, or something bespoke)?

6) What are your views on phasing the regulatory requirements for hydrogen under the CMA (e.g. focusing on prospecting/exploration permitting first)?

Hydrogen as a non-mineral natural resource

7) Do you support regulating natural and orange hydrogen as a non-mineral natural resource outside of the CMA?

8) What do you consider to be the advantages and disadvantages of this approach?

9) Do you consider the RMA is an appropriate tool to allocate and manage natural and orange hydrogen resources? If not, why not?

10) Do you prefer a bespoke regime over the RMA to allocate and manage natural and orange hydrogen resources? Please explain.

Other questions

11) Do you consider either approach a barrier to natural or orange hydrogen development in New Zealand?

12) Are there any other alternative regulatory approaches to develop natural or orange hydrogen in New Zealand?

13) Do you have views on how Māori rights and interests should be reflected in the regime?

Footnotes

[1] Noting that the Government’s resource management reform will replace the RMA with 2 pieces of legislation.

[2] This is a process that pools the interest of multiple landowners so that gas extraction is managed as a single unit, ensuring that each party receives a proportionate share of the production.

[3] New planning laws to end the culture of ‘no’(external link) — Beehive.govt.nz

< Broader regulatory framework | Next steps and having your say >