Weathertight homes – a bold response to regulatory failure

This case study examines the government response to disputes arising from a wide-scale regulatory failure.

On this page

About the case study

In this case study, a specific set of circumstances came together to create a situation where thousands of buildings were not weathertight.

It shows:

- the benefits of regularly reviewing a dispute resolution scheme to ensure that it is fit-for-purpose and operating effectively

- how the government can successfully ramp up its response as problems become more acute and widespread.

History of the issues

From the mid-1990s, some houses were built in a way that did not withstand weather conditions and did not comply with the New Zealand Building Code. These issues were the result of a specific combination of factors - a ‘perfect storm’ as it were: the Building Act 1991, which changed building controls from a prescriptive system to a performance-based regulation regime, the dropping of the apprenticeship training system, a design trend towards Mediterranean-style buildings, and a building boom.

A large number of timber-framed buildings constructed during this period (primarily between 1994 and 2004) were subsequently found to allow water into the building, which could lead to decay of the building materials. In extreme cases some buildings or building elements (such as decks) became structurally unsound. Some buildings also became unhealthy to live in, with mould and spores developing within the damp timber framing.

The total cost was estimated by a 2009 PricewaterhouseCoopers report as NZ$11.3 billion, for a consensus estimate of 42,000 affected buildings.

First response - legislative action

As awareness of the issue of leaky buildings grew, the scale and scope of the damage started to become apparent, and legislation was very quickly introduced to provide some additional redress and assistance to the owners of these buildings. The Weathertight Homes Resolution Services (WHRS) Act 2002 provided speedier and more flexible legal options and assistance than were available through existing dispute resolution avenues such as the Disputes Tribunal, or the court system.

A scheme in need of improvement

However, as time went on, the services available under the WHRS Act 2002 were criticised for being clunky, having an extensive backlog, and leaving home owners unprepared for the dispute resolution process. In particular, it was thought that having mediation as a separate step before filing for adjudication had not worked well.

The system had several self-limiting steps built into it, which created a specific set of complications. When home owners filed a claim there was always the option to settle by negotiation with the potential respondents as a first step, but many home owners were inexperienced, poorly prepared and didn’t know what they wanted. Often the adjudication and mediation service was initiated too early, and the delays and poor participation were a result of the inadequate preparation and understanding of exactly how the system worked.

Taking experts to mediation without being given prior notice of what they would be saying meant that some parties could be completely taken by surprise and overwhelmed by the situation. On some occasions the parties would settle, sometimes for less agreeable terms than they had hoped, in order to move on with their lives. Abandoning mediation was common.

There was also a sense that homeowners were sometimes reluctant to take the step that would see them locked into a formal system. This could be exacerbated by perceptions that other parties were operating in denial, taking no responsibility for the issues or had ulterior motives to keep the claim from settling. With the low levels of trust and other complicating factors, a claim could stay in mediation for months and drag on interminably for claimants.

Second response – updated legislation and the Weathertight Homes Tribunal

The Weathertight Homes Resolution Services Act 2006 came into force on 1 April 2007. It improved and refined the earlier process, drawing on knowledge gained from the implementation of the WHRS Act 2002.

The new Act included provisions for multi-unit claims (such as apartment buildings), established the Weathertight Homes Tribunal administered by the Ministry of Justice and introduced a streamlined system that included mediation as part of the Tribunal process. It also included new measures such as preliminary conferences and a fast-track process for resolving claims under $20,000. This new approach sought to be methodical, fair and to provide a better level of certainty.

Tribunal brings transparent, new approach

The Tribunal introduced significant change - most noticeably nothing went to mediation or adjudication until appropriate information was filed and preparation was complete.

Mediation proved most effective in deciding how to proceed, and in ensuring all parties entering negotiations knew exactly what would happen if settlement was not reached. This created a clear path to ensure that all parties had an understanding of the nature of the dispute and the possible outcomes.

This transparent process and better preparation also had a very positive knock-on effect. For example, the assessor’s report (an assessment of the leaky home by a WHRS assessor) had previously been the only real source of technical information. The introduction of expert conferencing meant that agreement could be reached on key points such as defects and quantum outside of a hearing. Many matters now settle as a result of an experts’ conference saving the need for hearing. If a hearing is still required, the conferences reduce the time required for the expert panel. This has made the process more efficient and cheaper for the parties as well as providing a new level of openness.

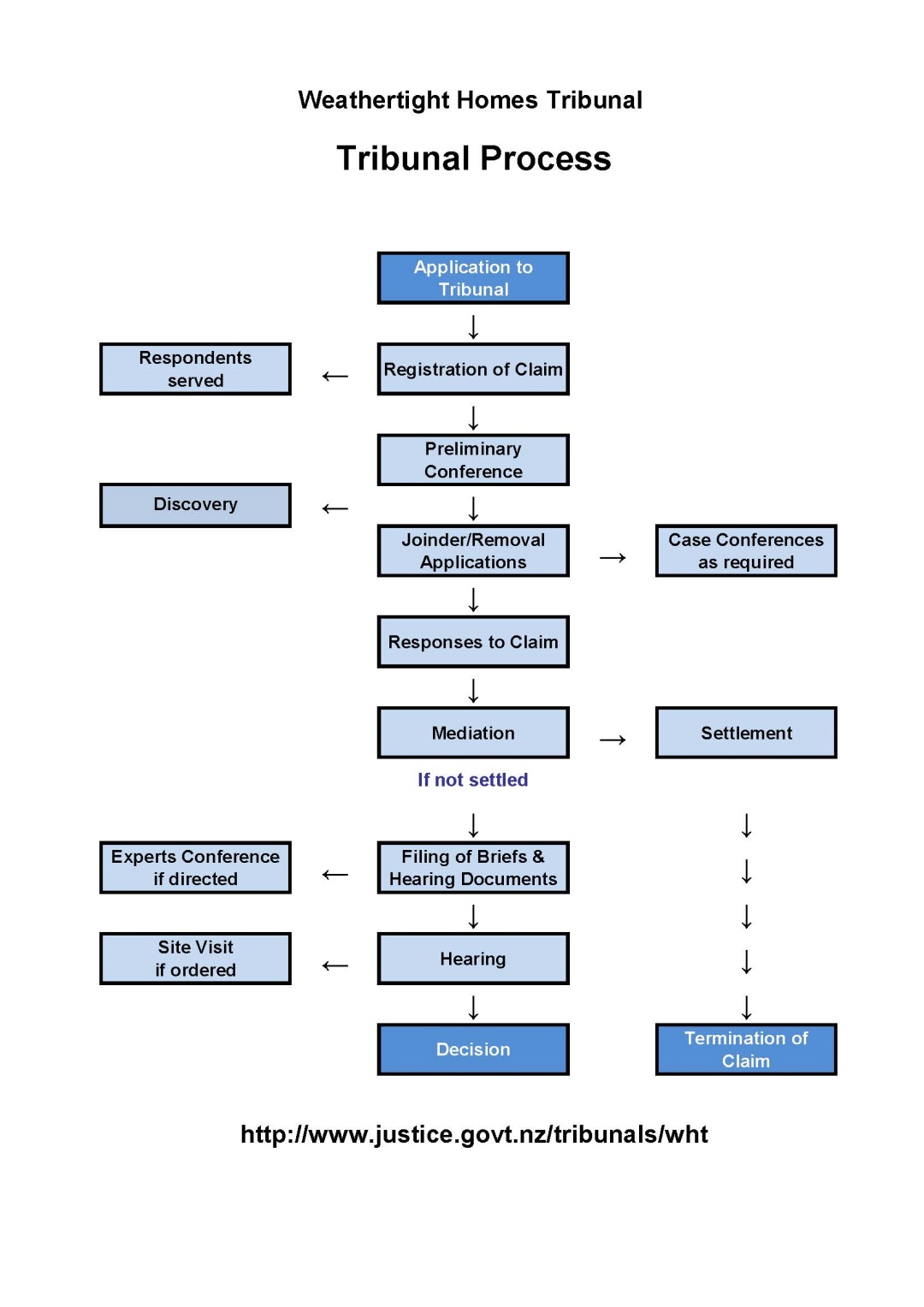

The Tribunal also introduced a stepped process which streamlined and clarified the proceedings:

- An application to bring a claim to the Tribunal is filed.

- A preliminary conference is convened at which a time-table is set and issues in the dispute identified.

- Disclosure by all parties of relevant documents.

- The Tribunal deals with applications to join or remove parties from the claim.

- Respondents state their defence and any expert evidence they intend to rely on at mediation or in the hearing.

- Mediation (if the parties agree) facilitated by MBIE. It is a confidential process and the Tribunal is only informed of the final outcome.

- Experts’ conferences (if ordered/directed). These are normally held just in advance of the adjudication.

- Adjudication hearing.

The new operating system for the Weathertight Homes Tribunal meant that almost immediately the resolution of these claims became faster. From the beginning approximately 90% of claims were settled, with 70% of these being settled at mediation. In the last few years the rate of resolution at mediation has risen to around 80-85%, with most of the balance settling between mediation and the hearing. Only 2-5% now go to hearing.

The Tribunal processes

The flowchart below shows the main stages of the Weathertight Homes Tribunal process. All claims going to the Tribunal follow these steps.