Chapter 3: How are land agreements made, and what rules are there around competition?

Land use and development is governed by a system of laws and rules

On this page

To understand how well our current system protects competition, we need to understand not only the Commerce Act 1986 and its laws specific to competition, but also the wider system of land use and development in New Zealand. This section looks at how land agreements are made and what procedures there are to protect competition.

When someone decides to develop land, they must engage with a system of rules that define how that land can be used

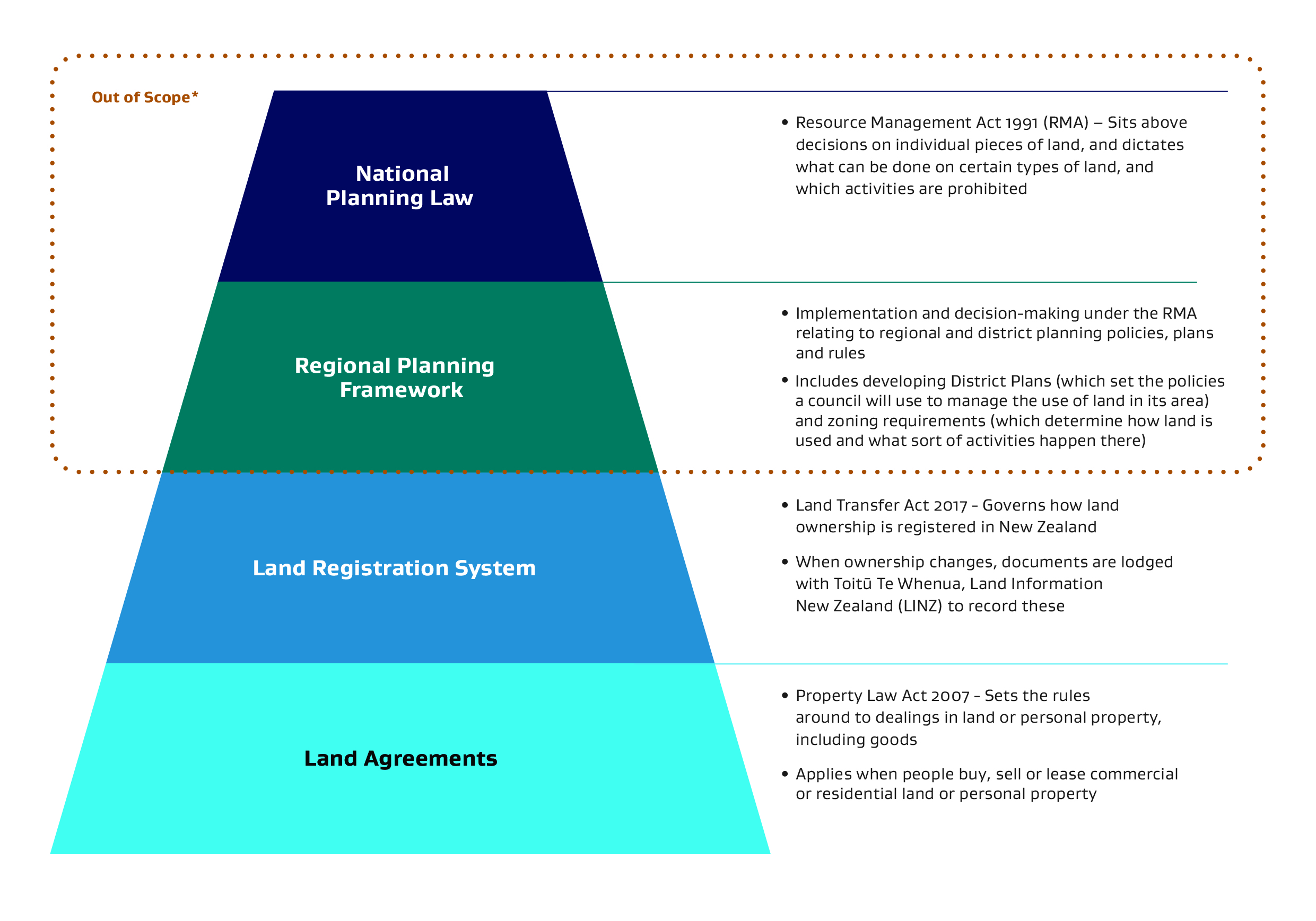

Some of these apply at a national level, others are defined by regional and district councils, and some are agreed between individual parties. Figure One below provides an overview of the interplay of the rules governing land development, and the different layers of how land use and development can be mandated or restricted.

Figure One: Rules governing land use and transfer

Text description of figure one: Rules governing land use and transfer graphic.

For the purposes of this work, we are interested in land agreements and the land registration system

There are 3 parts of the lifecycle of a land agreement that are relevant to this review:

The land agreement is created

The Property Law Act 2007 (Property Law Act) sets the rules around dealings in land or personal property, including goods. It applies when people buy, sell or lease commercial or residential land or personal property (for example, it details the law relating to the cancellation of agreements for sale and purchase).

While it is not a defined term in the Property Law Act, we use the term 'land agreement' in this document to include instruments such as covenants, easements and encumbrances where:

- one party is subject to restrictions or obligations they must comply with and

- another party benefits form the restrictions/ obligations and can compel compliance with them.

The land agreement is recorded on the Land Titles Register

When a property or section is sold, legal documents are lodged with Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand (LINZ), to record any changes made to records, such as transfers of ownership, discharges of mortgages and new mortgages.

The ‘Land Titles Register' [7] holds a record of all these changes. The records of title held in the Land Titles Register prove the ownership of land and confirms the site size, and the rights and restrictions that apply to the land. The Registrar-General of Land (RGL, part of LINZ) has specific responsibility for this, including for developing standards, setting an assurance programme and administering claims [8].

The accuracy of the Land Titles Register is an important part of our legal system: the title of a registered landowner is state guaranteed under the Land Transfer Act 2017 and is supported by a compensation regime under which damages may be paid by the Crown for loss arising from a registration error, guaranteed title search or title fraud.

We consider registration of land agreements is relevant to this review because:

- it provides a publicly searchable record of land agreements, which would otherwise be visible only to the parties involved

- it is the first point at which government has sight of private land agreements

- registration can determine whether a land agreement is enforceable against future owners or occupiers of the land. For example, once recorded on the Land Titles Register, a land covenant will ‘run with the land’, meaning that it will bind any third parties who subsequently acquire (or lease) that land.

The land agreement is enforced

There are generally 2 parties involved in a land agreement: one that must comply with the terms of the agreement, and one that receives the benefit of that compliance. The party subject to restrictions or obligations is required to comply and penalties may be imposed if they fail to do so.

The Property Law Act gives the latter the power to enforce certain types of agreements (for example, compel the first party to comply), including covenants and easements. Enforcement takes place between parties, and through the court system if there is disagreement.

Registrations of a land agreement on the land Titles Register may not affect whether the agreement is enforceable. For example, if a covenant does not comply with the law, then a party will not be able to compel another to comply, regardless of whether it has been recorded on the Register.

Question 16

If you are party to a land agreement, did you record this agreement with LINZ? What type of agreement is it?

A note on national and regional planning frameworks and their relevance to this work:

There are rules specific to competition in New Zealand

The Commerce Act 1986 (the Commerce Act) aims to promote competition in markets for the long-term benefit of consumers. It seeks to enable businesses to compete fairly on their merits and for the Commerce Commission, as the regulatory body that administers and enforces the Commerce Act, to take action against anti-competitive conduct. This section describes the parts of the Commerce Act that prohibit agreements that could lessen competition, and what we can do when these are broken.

General prohibitions on agreements which lessen competition

Sections 27 and 28 of the Commerce Act prohibit covenants and contracts that harm competition. The main difference is that section 28 is specific to covenants, while section 27 applies to a ‘contract, arrangement or understanding’:

- section 27 of the Act provides that no person may enter into or give effect to a contract, arrangement or understanding containing a provision that has the purpose, effect, or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a market and

- section 28 provides that no person may require, or give, or enforce, a covenant that has the purpose, effect, or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a market.

These sections have the potential to cover a wider range of agreements, both:

- those with the purpose of substantially lessening competition, which would include an intention or aim to be anti-competitive and

- those with the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition, which could include those where the purpose is not to restrict competition, but which apply in such a way that it has an actual or potential restrictive effect, intended or not.

The consequence for contravention of these prohibitions is that the covenant would be unenforceable. Pecuniary penalties and other sanctions, such as damages, may also be imposed by the Court, and, on finding a contravention, the Court may vary the contract or covenant.

Grocery retailers are subject to more specific rules

In 2022, in response to the Commerce Commission’s retail grocery market study, the Commerce Act was amended to prohibit covenants which restrict the availability of suitable sites for grocery retailers [10]. It also made existing covenants unenforceable. To do this, section 28A provides that a covenant, contract, agreement, exclusivity covenant or other provision in a lease that impedes, or is likely to have the effect of impeding, the development or use of land or a site as a grocery retail store (or relevant competitor) will be deemed as having the purpose or effect of substantially reducing competition in the relevant market. By deeming these to reduce competition, it means they now contravene section 27 or 28 of the Commerce Act, without the need to assess their impact on competition.

No covenant can contain a cartel provision

Changes that came into force in April 2023 prohibit covenants that contain a ‘cartel provision’. A cartel provision is one that fixes prices, restricts output, or allocates markets for goods or services that are supplied or acquired by the parties to the covenant in competition with each other. Section 30 of the Commerce Act now makes it clear that covenants or other agreements between competitors which are intended to limit competition are not lawful.

There are some limited exceptions to these provisions, the main one being to allow for collaborative activity that does not have the dominant purpose of lessening competition.

Businesses can apply for authorisation for land agreements

Under the Commerce Act, businesses can apply to the Commission for ‘authorisation’ of an agreement or covenant that might breach the provisions of the Commerce Act which prohibit anti-competitive conduct. Authorisation allows firms to undertake conduct that would otherwise breach the Commerce Act, and the Commission will grant authorisation when it is satisfied that the public benefit of the agreement outweighs the competitive harms [11].

New Zealand’s courts have defined a public benefit as: anything of value to the community generally, any contribution to the aims pursued by the society including as one of its principal elements (in the context of trade practices legislation) the achievement of the economic goals of efficiency and progress.

Agreements and covenants prohibited under sections 27 and 28 of the Commerce Act are both included in the Commission’s authorisation regime. The Commission can authorise agreements subject to conditions and for a time period it considers appropriate, and it also has the power to vary and revoke authorisations in certain circumstances.

[7] Registration and land transfer services are delivered through an electronic workspace known as ‘Landonline’, but this document refers to the ‘Land Titles Register’ as a concept.

[8] Supplementary Information on the responsibilities of LINZ’s statutory officers(external link) — Beehive.govt.nz

[9] Unitary authorities such as Auckland Council or Marlborough District Council, have the functions of both a regional council and a territorial local authority; territorial local authorities are generally city and district councils (refer s5 Local Government Act 2002).

[10] Commerce (Grocery Sector Covenants) Amendment Bill(external link) — Legislation New Zealand

[11] Updated Authorisation guidelines, Commerce Commission, December 2020:

Authorisation Guidelines December 2020(external link) — Commerce Commission New Zealand