Chapter 2: The Customer and Product Data Bill - technical matters and system settings

On this page

147. We invite feedback on all aspects of the draft law. This Chapter:

- provides more information about some technical matters, and asks questions on specific details to ensure the draft law works well, and

- outlines regulatory settings including dispute resolution, powers and penalties, and the proposed regulators.

Structure of the draft law

Part 1: Preliminary provisions

Part 1 contains preliminary provisions. This includes clauses that cover the purpose and interpretation of the draft law, and the draft law’s territorial application and application to the Crown.

Part 2: Regulated data services

Part 2 contains the main obligations for data holders and accredited requestors.

Part 3: Protections

Part 3 contains:

- requirements about customers’ consent and verification of their identity

- provisions regarding notification, transparency of data policies, record keeping, complaints, and the relationship with other legislation such as the Privacy Act and the Official Information Act.

Part 4: Regulatory and enforcement matters

Part 4 contains regulatory and enforcement powers and penalties.

Part 5: Administrative matters

Part 5 enables and sets the process for:

- the draft law being “turned on” for each sector to which it will apply

- accredited requestors to apply for and receive accreditation

- a public register of designated and accredited entities.

- any cost recovery of government functions

- standard making and exemptions

- regulations.

Schedule

This will contain transitional, savings and related provisions (if required).

Part 1: Preliminary provisions

Purpose

148. Clause 3 provides the purpose statement of the draft law. It sets out the immediate and longer-term outcomes that the framework seeks to achieve.

Question 21: What is your feedback on the purpose statement?

Definition

149. Our draft law, Australia’s consumer data right, and the Payments NZ API Centre’s standards each use different words to describe similar concepts. The table below shows how the words in the draft Bill relate to the words used in these other regimes. This table also aims to clarify where certain concepts do not have direct equivalents.

| Terms | Concept | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NZ draft law | Australia CDR | API Centre Standards | |

| Accredited requestor (clause 7) | Accredited data recipient (also called a consumer data right provider or provider) |

Third party | A business which is accredited to request a data holder provide data or give effect to an action. While other businesses (who are not accredited) can request data or actions, data holders do not have to respond to the request. Data holders are only required to respond to a request when the request comes from an accredited requestor. |

| Accredited action initiator | |||

| Data holder (clause 6) | Data holder |

Provider | A business which holds the data, or is capable of giving effect to the action, which an accredited requestor has requested. Only designated businesses holding designated data are considered data holders for the purposes of the draft law. |

| Action service provider | |||

| Outsourced provider (clause 21) | No equivalent | No equivalent | A business which helps a data holder or accredited requestor perform their duties or powers under the draft law. The definition is broad and captures a range of tasks and different kinds of help that a business might assist with. For example, an outsourced provider might:

|

| No equivalent | Intermediary | No equivalent | A business which helps accredited requestors collect data from data holders. Intermediaries are an Australian regulatory concept and do not appear in the draft law. However, some kinds of actions an intermediary might do in Australia are caught under the definition of outsourced provider in New Zealand’s draft law. |

| No equivalent | Affiliate | No equivalent | A class of accreditation which is used in Australia. Businesses can become an affiliate when they are ‘sponsored’ by an accredited requestor. Affiliates can request data from a data holder as if they were accredited themselves. |

| No equivalent | CDR representative | No equivalent | A business which is not accredited to request data or actions, but is allowed to handle consumer data. The Australian CDR regime sets rules around who may be a CDR representative and how a business can become one. In Australia, accredited requestors can only ask other businesses to handle data (store it, clean it, or help an accredited requestor use it) if the other business is a CDR representative. In New Zealand, accredited requestors can employ the services of outsourced providers to do these things, as long as they comply with the Privacy Act. The draft law includes the ability to make regulations relating to outsourced providers. No specific requirements are currently considered to be necessary, but the power has been included in case it is needed in future. |

Data

150. The term ‘data’ is not defined. The draft law notes that data includes information, and personal information within the meaning of the Privacy Act.

151. The intention is for the term to include derived data, and data derived from derived data. The designation regulations will identify which customer and product data, and which data holders become subject to the draft law, following the process set out in clauses 59 to 63.

Directors and senior managers

152. The term director has the same meaning as in Section 6 of the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.

153. Similarly, senior manager, in relation to person (A), means a person who is not a director but occupies a position that allows that person to exercise significant influence over the management or administration of A (for example, a chief executive or chief financial officer).

154. The definitions of director and senior manager have two purposes in the draft law:

- They are relied on when providing for who may authorise data exchange on behalf of customers who are businesses.

- One of the proposed accreditation criteria is a ‘fit and proper person’ test for directors and senior managers of accredited requestors. The definitions are in line with the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act and Financial Markets Conduct Act to enable the ability for a ‘fast track’ process for this criterion, where an entity’s directors and senior managers have already been considered a fit and proper person under those laws. See paragraph 101 of Chapter 1.

Territorial application

155. The draft law would apply in respect of designated customer data or designated product data held by those who carry on business in New Zealand.

156. It does not matter where the data is collected or held, or where the customer or product concerned is located.

157. A business can be treated as carrying on business in New Zealand without necessarily:

- being a commercial operation

- having a place of business in New Zealand

- receiving payment for goods or services

- intending to make a profit from its business in New Zealand.

158. This proposed scope of application is based on that of the Privacy Act. It is important to note that in practice, the application of the draft law’s requirements will be limited to those who either apply for accreditation, or who are brought into the scheme via designation regulations.

Question 22: Do you agree with the territorial application? If not, what would you change and why?

Part 2: Regulated data services

159. Part 2 of the draft law includes the obligations that apply to data holders, and provides for specific rules to be set around joint account holders and secondary users. It also provides for obligations in relation to ‘outsourced providers’.

Joint customers (clause 19) and secondary users (clause 22)

160. The draft law needs to cover a wide range of customers, including individuals, businesses and other entities.

161. Many customers hold accounts jointly with another person, such as their spouse. Other customers are businesses or trusts, and will have different needs to individuals in relation to giving and managing consents for the exchange of their data. For example, a customer which is a business may need different permissions for staff in accounts, and for its chief financial officer.

162. This is why the draft law provides that data holders and accredited requestors may be required to maintain systems or processes for dealing with secondary users and joint customers. The detailed requirements for this functionality will vary by sector, and will be provided for in regulations.

163. We acknowledge that many data holders already have systems or processes in place for dealing with secondary users and note that these will be considered during the designation process. This will help ensure that as many types of customers as possible can benefit from regulated consumer data services.

Electronic system

164. Clause 26 of the draft law proposes that regulated data services must be provided electronically and in the way prescribed by the regulations and standards. This is a core requirement of the draft law – ensuring that data is exchanged efficiently, securely, and with standard formats and safeguards.

165. The draft law provides for a broad range of matters which the rules and standards may cover, however not all of them will require a standard or a rule to be created in the first instance. Security of the exchange process, and standard formats will, however, be essential.

Reasons to refuse access to customer data or to carry out an action

166. The draft law proposes that if a customer or an accredited requestor makes a valid request for designated customer data, or to perform an action, then this must be provided or performed.

167. We would like feedback on how best to align this requirement with existing obligations and safeguards:

- Regarding automated access to customer data, existing practices and protections in the Privacy Act allow access to data to be refused in some cases, including but not limited to if the data holder has reasonable grounds to believe that the request is made under the threat of physical or mental harm (section 57(b) of the Privacy Act) or if the disclosure of the information would cause harm to an individual (in the categories set out in section 49 of the Privacy Act).

- Regarding the performance of an action, existing practices and common contract terms which allow the refusal to act on instructions where they have good reason to do so, such as where there is a risk of fraud.

Question 23: Do you think it is appropriate that the draft law does not allow a data holder to decline a valid request?

Question 24: How do automated data services currently address considerations for refusing access to data, such as on grounds in sections 49 and 57(b) of the Privacy Act?

Part 3: Protections

168. Part 3 of the draft law includes the key safeguards which should be part of customer data exchange in any sector. These include the requirement for customer consent, the ability for customers to easily view and withdraw consent, the requirement for authentication of customers’ identity and for certain notifications. They also include the following, which are discussed in more detail below:

- record keeping

- customer data policy

- complaints.

Data holders and accredited requestors must keep certain records

169. The draft law provides that a data holder and accredited requestors must keep records of a range of matters.

170. The purpose of these record keeping requirements is to enable monitoring of data holder and accredited requestor compliance, to support enforcement. For example, in the event of a reported breach MBIE or the Privacy Commissioner could request these records as part of their investigation. If this record keeping requirement requires the development of new systems and storage we expect it would incur compliance costs, however, we also consider that record keeping would improve consumer protection and trust in the system.

171. We note that the provisions do not require the storage of the customer information itself. The draft law proposes that records must be kept by data holders and accredited requestors for five years.

Question 25: Are the proposed record keeping requirements in the draft law well targeted to enabling monitoring and enforcement? Are there more efficient or effective record keeping requirements to this end?

Data holders and accredited requestors must have customer data policy

172. The draft law requires data holders and accredited requestors to develop, publish, implement and maintain policies relating to customer, product and action requests.

173. These policies are intended to help customers choose whether to do business with a data holder or accredited requestor based on how customer data is managed. We think customers will want to know the following:

- For both data holders and accredited requestors:

- how a customer can complain about compliance with obligations in the Bill

- the complaints process

- the name of any outsourced providers used, the nature of the services provided, and the type of data used or held by them; potentially also what checks are carried out before using an outsourced provider

- whether any customer data or insights from customer data are rented or on-sold, and if so, for what purposes, and in what manner (including how it is de-identified prior to being shared further).

- For accredited requestors only, we propose the policy must also contain:

- what class of designated customer data or designated action the accredited requestor is accredited for.

- For data holders only, we propose it must also contain:

- what designated customer and product data they hold, and what designated actions they must perform.

Question 26: What are your views on the potential data policy requirements? Is there anything you would add or remove?

Complaints

174. Clause 43 sets out requirements relating to the complaints process that data holders and accredited requestors must have. The early resolution of complaints is beneficial to all parties.

175. We expect that many data holders will already have customer complaints processes in place and therefore this requirement will not impose significant additional costs (if any). However, some accredited requestors may need to establish customer complaints processes to comply with this requirement. This will incur a compliance cost.

176. When a sector is designated, we propose that accompanying regulations will require customer complaints to be referred to existing industry dispute resolution bodies when these have not been resolved in the internal complaints process.

Part 4: Regulatory and enforcement matters

177. Part 4 contains regulatory and enforcement powers and penalties. We note that much of this part is not included the draft law at present. These provisions will depend on the final form of the main obligations.

Regulatory powers

178. Currently, the Privacy Commissioner has broad responsibility under the Privacy Act to monitor and enforce compliance with the Privacy Act, including own-motion investigations, providing redress for breaches of an individual’s privacy and receiving reports of notifiable privacy breaches. The Privacy Commissioner will continue to have the role of compliance and enforcement of privacy matters to the extent that breaches of this new legislation are also breaches of the Privacy Act, including in setting expectations through guidance and (if necessary) Commissioner-issued Codes of Practice (akin to regulations).

179. However, a specific enforcement agency with appropriate regulatory powers for compliance and enforcement is necessary to uphold the obligations in the draft law (beyond those which would be covered in the Privacy Act) and to ensure the integrity of the new system.

MBIE’s chief executive may require person to supply information, produce documents, or give evidence

180. Clause 49 introduces information gathering powers to ensure that MBIE is able to effectively monitor and enforce the draft law’s obligations on data holders and requestors.

181. These requirements are similar to the information gathering powers in the Australian CDR regime.[29]

Question 27: Are there any additional information gathering powers that MBIE will require to investigate and prosecute a breach?

Part 5: Administrative matters

182. Part 5 of the draft law contains provisions which enable and set the process for, among other things, designation, regulations and standards, government fees and levies, reporting requirements, and the operation of a register of data holders and accredited requestors. These are discussed in more detail below.

Designation process

183. A person or a class of persons (in effect a sector) may be designated as data holders through regulations made by the Governor-General on recommendation of the Minister.

184. Clause 60 of the draft law provides that the Minister must have regard to certain matters before recommending that designation regulations be made. This includes the interests of customers, including Māori customers, and the impacts and benefits for data holders.

185. We consider that these specific considerations are necessary in addition to standard Regulatory Impact Assessment considerations because of the significant investment required by data holders to comply with the draft law.

Question 28: Are the matters listed in clause 60 of the draft law the right balance of matters for the Minister to consider before recommending designation?

Note on context for designation process

186. Proposed designations will come after dedicated rounds of engagement on:

- the proposed data, and data holders

- the text of the proposed designation regulations, and the implementation plan for a sector – including the sequencing of mandatory functionality within that sector.

187. The first sector which will be designated is banking. The criteria that the Government took into account when deciding to prioritise banking for designation were:

- opportunities or benefits that a designation could realise and problems it could solve or mitigate in the sector

- ease and speed of implementation

- whether data sharing in the sector is likely without regulatory intervention.

188. These criteria will continue to be relevant when considering which sectors to bring into the system next.

Giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi in decision making

189. Te Tiriti/The Treaty creates a basis for civil government extending over all New Zealanders, on the basis of protections and acknowledgements of Māori rights and interests within that shared citizenry.

190. To give effect to Te Tiriti/the Treaty when making decisions about regulations and standards,[30] the draft law proposes an approach similar to that in the sections 21 and 47(2)(a) of the DISTF Act. This alignment will assist with consistency, and reducing complexity and cost for government, iwi, hapū and other participants in the system.

191. To align with the DISTF Act the draft law provides:

- procedural requirements before regulation and standard making. It requires consultation with iwi, hapū and Māori organisations, as well as with tikanga experts who have knowledge of te ao Māori approaches to data governance (see clauses 61 and 88 of the draft law)

- specific considerations during the making of technical standards or their incorporation by reference. MBIE (through its chief executive) must have regard to whether the material is consistent with tikanga Māori in relation to data governance (see clause 89 of the draft law).

192. The draft law also proposes that the Minister must have regard to (among other considerations) the following matters before designating data (see clause 60 of the draft law):

- the interests of customers, including Māori customers

- the sensitivity of the data. This could include whether it is tapu.

Question 29: What is your feedback on the proposed approach to meeting Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi obligations in relation to decision-making by Ministers and officials?

Government fees and levies

193. The draft law will enable the imposition of levies, as well as some cost recovery through accreditation fees.

194. No policy decisions have been made regarding the appropriate extent or timing of cost recovery. We are aware that significant investment will likely be required from data holders and potentially also accredited requestors in order to participate. This cost to participate will be a key consideration when developing any cost recovery approach. Engagement and consultation on these matters will take place in due course.

Register of data holders and accredited requestors

195. The draft law enables MBIE to maintain a publicly accessible register of data holders and accredited requestors. This is important for transparency and accountability.

196. The draft law also provides for MBIE to maintain a closed register accessible only to data holders and accredited requestors. This register will have machine-readable interfaces for automated access and use, eg to check whether a data holder is currently able to respond to data requests, or whether a requestor is accredited.

197. We would like to know what further information would be of particular assistance to data holders and accredited requestors to include on the closed register.

Question 30: What should the closed register for data holders and accredited requestors contain to be of most use to participants?

Question 31: Which additional information in the closed register should be machine-readable?

Reporting requirements

198. The draft law proposes a fixed date for annual reporting for accredited requestors, to ensure a consistent basis for measuring performance of the regulated data system overall.

199. A reporting date of 31 October for the period ending on 30 June each year has been proposed, to be away from financial year and tax reporting deadlines.

200. The measures which must be reported annually will be defined in due course. We imagine they will include the number of customers requesting access to their data or requesting action initiation, and transaction volumes.

201. There may also be an opportunity for data holders to provide real-time reporting to the enforcement agency. This could cover the performance of data holder APIs in a frequent, automated manner, to ensure system health and promote accountability. This would be similar to the requirement on data holders in the Australian CDR.[31] Clause 26(2)(h) in the draft law enables this kind of requirement to be introduced. We seek your feedback on this idea.

Question 32: Is a yearly reporting date of 31 October for the period ending 30 June suitable? What alternative annual reporting period could be more practical?

Question 33: Should there be a requirement for data holders to provide real-time reporting on the performance of their CDR APIs? Why or why not?

Specifying customer refunds or redress in regulations – nature of cap

202. The draft law enables requirements to be set in regulations allowing for customer refunds or redress in some circumstances. Such requirements will provide clear accountability and processes in cases of error or delay in action initiation (eg a payment error causes the customer to be charged a late fee). Similar regulations are in place in the United Kingdom.[32]

203. For this kind of requirement to be suitable for regulations (rather than the Act itself) it may be necessary to include a cap on the amount which can be required to be repaid. This amount could be reviewed and adjusted by the Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs, in line with the Consumer Price Index, as with the approach taken in the Financial Reporting Act 2013[33] or else it could be indexed or tethered to the Consumer Price Index.

Question 34: What is your feedback on the proposal to cap customer redress which could be made available under the regulations, in case of breach?

B. System settings

Regulators

204. MBIE will be responsible for standard setting, accrediting requestors, operating the register, and promoting the use and uptake of regulated data services. MBIE will also be responsible for compliance and enforcement functions under the draft law.

205. Where breaches relate to personal information, the Privacy Commissioner and Human Rights Review Tribunal will also have a compliance and enforcement remit under the Privacy Act.

206. A Memorandum of Understanding between MBIE and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner will clarify the roles and processes of the two regulators where both privacy and non-privacy considerations are involved.

Complaints and dispute resolution

207. While there are protections in place for customers under the draft law, issues between customers, data holders and accredited requestors will still arise at times. It is therefore important to have a way to resolve these issues quickly and effectively.

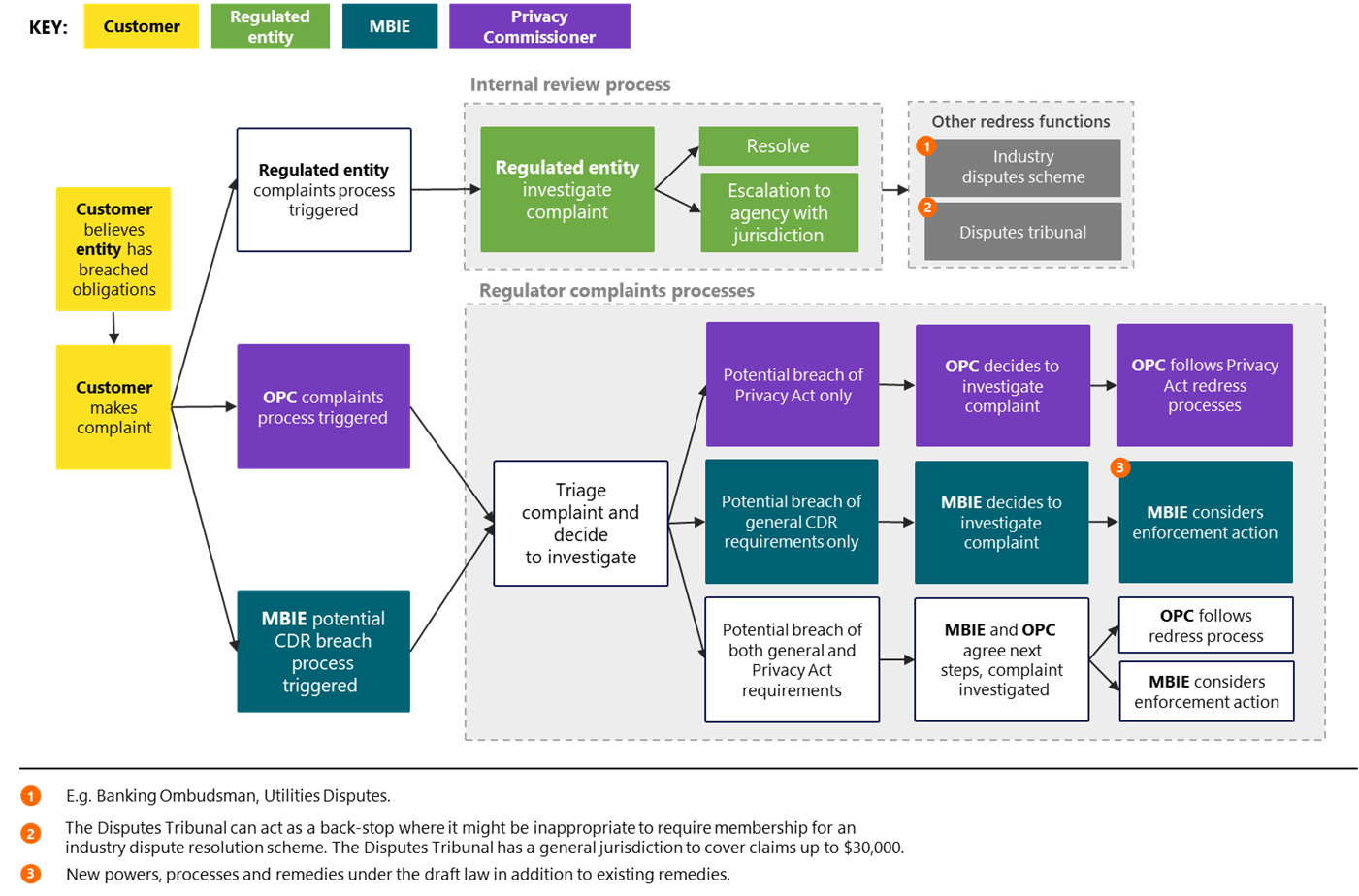

208. Complaints can be made to accredited requestors and data holders, or else to the regulators. The following diagram shows an overview of the complaints system. This is then discussed in more detail below.

Overview of the complaints system

Text description of image

Privacy-related complaints to regulators

209. We expect that many of the complaints that customers will have about regulated entities will be privacy related. These will follow the current process for privacy complaints.

210. Where a complaint relates to personal information or breaches of the Privacy Act IPPs[34] it will be dealt with by the Privacy Commissioner using their existing powers, systems and processes. The Privacy Commissioner will encourage parties to settle complaints using conciliations, even where they do not investigate. Where the Privacy Commissioner is unable to resolve the issue, they will close the complaint and provide a certificate that can be used to take the case to the Human Rights Review Tribunal.

Other complaints to regulators

211. Where a complaint to regulators relates to a situation where the Privacy Act does not apply (eg the customer is a company, and personal information is not involved), this will be dealt with by MBIE as the enforcement agency.

212. There will be cases in which the Privacy Commissioner’s and MBIE’s jurisdictions overlap (eg a participant has not complied with a security standard and this has resulted in the unauthorised disclosure of personal information). A Memorandum of Understanding will clarify the roles and processes of the two regulators where both privacy and non-privacy considerations are involved. To support the functioning of this relationship, the Privacy Commissioner and MBIE must be able to share information to assess the case and refer complaints to one another where appropriate. Following consultation, the necessary information sharing provisions will be developed for inclusion in the draft law.

Customer complaints to data holders or accredited requestors

213. The draft law requires that data holders and accredited requestors have an internal process to resolve customer complaints (see clause 43 of the draft law).

214. Customers whose complaints are not resolved during the internal process should have the option of taking their complaint to an independent external dispute resolution scheme. These schemes provide a low-cost way to resolve disputes when compared to taking court action. Unless special provision is made in our draft law, many unresolved complaints would only be able to be pursued through the courts.

215. Non-privacy complaints about breaches of the draft law’s obligations will be dealt with by existing industry dispute resolution schemes within the designated sector. For example, in the banking sector a non-privacy complaint about a bank’s regulated data services would be considered by the Banking Ombudsman, if it was not able to be resolved using the bank’s internal complaint process.

216. This approach is preferred over establishing a dedicated new dispute resolution scheme for regulated data services. It will avoid complexity and be easier for customers to navigate.

217. However, some accredited requestors may not have existing obligations to be members of an industry dispute resolution scheme. To ensure all customers have access to independent dispute resolution services, we consider that a similar approach to the Australian CDR[35] could be given effect through regulations, during the designation process. Both data holders and accredited requestors would be required to be a member of the relevant industry dispute resolution scheme.

218. This approach would make it easier for customers to navigate and ensure consistent and fair options for redress. However, it would impose additional costs on accredited requestors and data holders to be members of dispute resolution schemes and may, depending on the number of complaints, require upskilling and resourcing for the relevant industry dispute resolution schemes.

219. In cases where it is inappropriate to require data holders and accredited requestors to be members of an industry dispute resolution scheme, we consider that the Disputes Tribunal[36] could be a built-in back stop in the draft law. This reflects that complaints about non-privacy matters under the draft law will often also be actionable under other legislation, such as the Consumer Guarantees Act and the Fair Trading Act, or under contract, where the Disputes Tribunal has existing jurisdiction.

Question 35: In cases where a data holder or requestor is not already required to be member of a dispute resolution scheme, do you agree that disputes between customers and data holders and/or accredited requestors should be dealt with through existing industry dispute resolution schemes, with the Disputes Tribunal as a backstop? Why or why not?

Powers, penalties and liability

220. MBIE has a compliance and enforcement function. Where breaches relate to personal information, the Privacy Commissioner and Human Rights Review Tribunal also have a compliance and enforcement remit under the Privacy Act.

221. The draft law will include a range of enforcement options, including infringement offences, compensation orders, pecuniary penalties and criminal offences. These are outlined in the table below and will be drafted after the main obligations and protections are finalised.

| Regulator | Liability tier | Penalty | Breach |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBIE | Tier 1 | Infringement notice of up to $20,000. Infringement offence of up to $50,000. |

Failure to maintain transaction records. Breach of notification or disclosure requirements (eg notification about how customers make a complaint, notification that transfer of data is complete). |

| Tier 2 | For a body corporate, a pecuniary penalty of up to $600,000. For an individual, a pecuniary penalty of up to $200,000. Compensation orders awarded through civil action. |

Failure to maintain transaction records. Breach of notification or disclosure requirements (eg notification about how customers make a complaint, notification that transfer of data is complete). |

|

| Tier 3 | For a body corporate, a pecuniary penalty of up to $2,500,000. For an individual, a pecuniary penalty of up to $500,000. Compensation orders awarded through civil action. |

Data holder fails to provide a CDR service to customers and accredited persons. A person misleads or deceives another person into believing either that a person is a CDR customer for CDR data, or a person is making a valid request for the disclosure of CDR data. |

|

| Tier 4 | For a body corporate, punishable on conviction by a fine of no more than $5,000,000 or either:

|

A person knowingly/intentionally/recklessly misleads or deceives another person into believing either that a person is a CDR customer for CDR data, or a person making a valid request for the disclosure of CDR data. A person fraudulently holds out that they are an accredited person (or particular type of accredited person). |

222. For contraventions of civil penalty provisions, we propose an approach to liability similar to that used in Australia. In Australia, a person who suffers loss or damage by conduct which contravenes a civil penalty provision may recover the amount of loss or damage by action against that person (or any other person involved in the contravention).[37]

223. The draft law does not include a provision equivalent to section 56GC of the Australian Competition and Consumer Act. This provides protection from civil and criminal liability where an entity complied with the Act, in good faith. We do not consider this provision to be necessary as compliance with an Act should not, as a matter of law, create liability.

Footnotes

[29] Section 56BI(2) of the Australian Competition and Consumer Act 2010 and rule 9.6 of the Competition and Consumer (Consumer Data Right) Rules 2020 give power to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission or Information Commissioner to give written notice to produce copies of records or information for such records.

[30] As noted in Chapter 1, the nature of requirements in the regulations, and the use cases which are enabled by the CDR are both relevant to Te Tiriti/Treaty obligations. Thoughtful design of user experience and interfaces are also relevant as they can help to ensure the system is accessible and unlocks value for all.

[31] Under the Australian CDR data holders report information to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission regarding performance and availability as set out in the Consumer Data Standards. See the dashboard here: https://www.cdr.gov.au/performance(external link).

[32] See clauses 91-94 of the UK’s Payment Services Regulation 2017.

[33] Under sections 48 and 49 of the Financial Reporting Act 2013 the Minister must regularly review amounts for the purposes of determining whether or not to recommend that an adjustment be made to take into account any increase in the CPI during the period to which the review relates.

[34] Breaches may include but are not limited to the collection of information without a lawful purpose (IPP 1), failure to take reasonable steps to make an individual aware of key information about collection (IPP 3), or inadequate measures around the storage or security of information (IPP 5) https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2020/0031/latest/LMS23342.html(external link).

[35] Under rule 6.2. of the Australian Competition and Consumer (Consumer Data Right) Rules 2020 data holders and accredited persons are required to be members of recognised external dispute resolution scheme in relation to CDR consumer complaints.

[36] See https://www.disputestribunal.govt.nz/about-2/(external link) for more information about the Disputes Tribunal.

[37] See section 82 of the Australian Competition and Consumer Act.