Chapter 1: Overview and key issues for the proposed customer and product data framework

On this page

20. This chapter provides a map of the proposed customer and product data framework and illustrates some key roles in the system. It also describes:

- how the draft law will fit with other laws such as the Privacy Act, and with Te Tiriti/the Treaty

- the proposed scope of the framework.

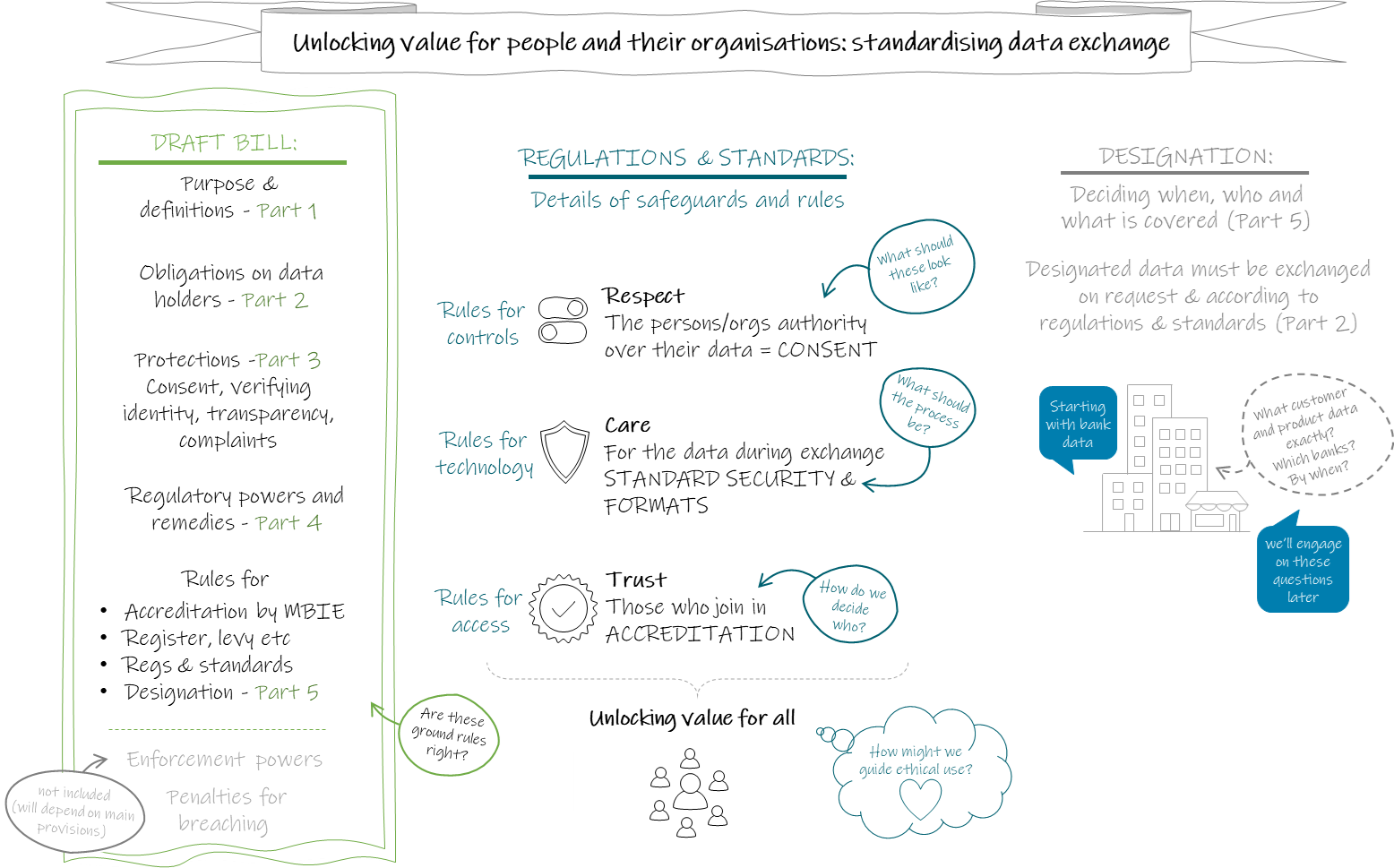

Map of the draft law

21. The draft law will become an Act of Parliament, containing key definitions protections and powers. It will eventually be accompanied by:

- regulations containing detailed rules, including which data is designated into the system

- standards, containing highly technical specifications.

22. In different parts of the discussion document we will be asking questions about the wording of the draft law, the content of the future regulations, and how technical standards should be set. Feedback on these will help get the ‘ground rules’ right in the draft law.

23. The draft law aims to improve the way that customer data is exchanged, but it will rely on existing laws and obligations relating to data and information, wherever possible.

24. The map on the next page shows the key elements, and the questions we have about each. This is followed by an illustration of the key roles in the system, and how they interact with each other.

Text description of image

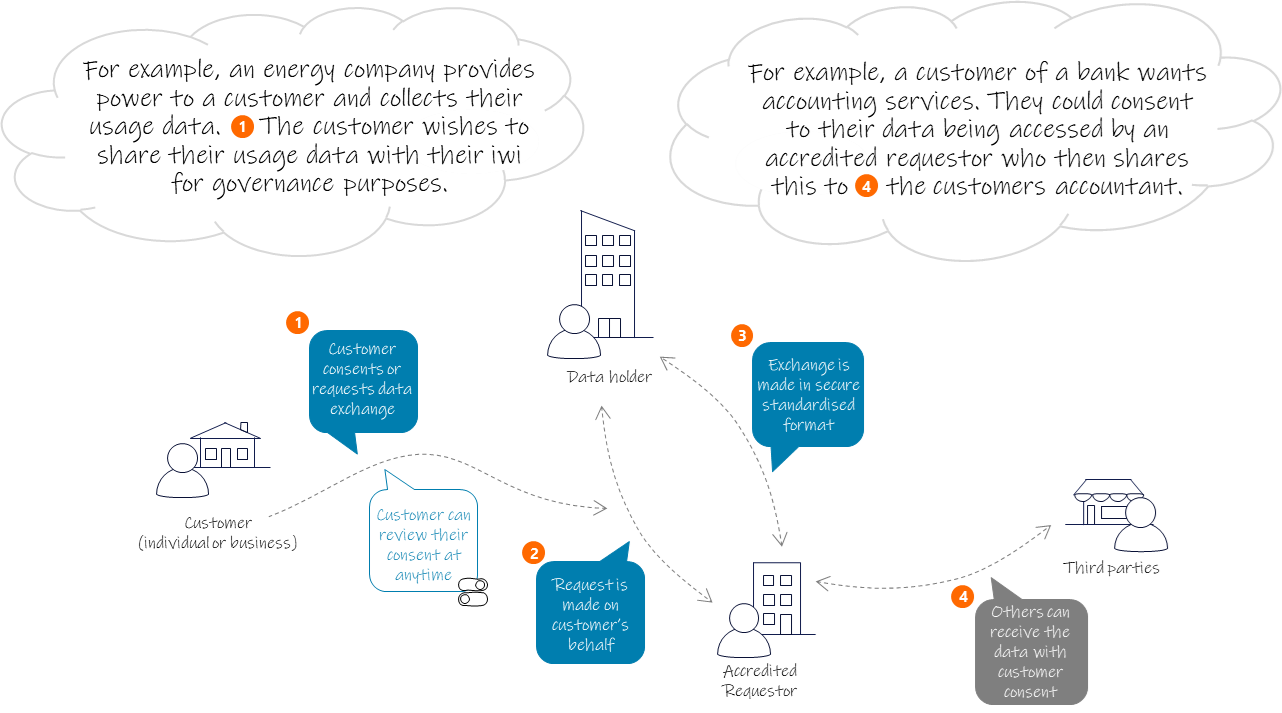

Illustration of key roles

Text description of image

How will the draft law interact with protections under the Privacy Act?

25. The Privacy Act provides rights and obligations around ‘personal information’, which is information about an identifiable individual. It protects personal information by requiring secure handling and storage of personal information, and protecting the collection, retention, use, accuracy and disclosure of our personal information. It ensures individuals can access and seek correction of their own personal information, as well as allows representatives to seek access and correction to the individual’s personal information.

26. The Privacy Act applies across the economy, including to any person, business or organisation. Therefore, the draft law relies on existing Privacy Act protections. These are not replicated in the draft law unless:

- the draft law provides the same protection as a privacy principle but sets a more specific requirement for customer data, or

- an equivalent Privacy Act protection is required in the draft law to ensure consistent treatment of all customer data (whether or not it is personal information). Consistent treatment is important to ensure simplicity, cost effectiveness, and to ensure sensitive commercial information also has protection.

27. The draft law covers all customer data, which includes data that relates to an identifiable customer (eg trusts, companies). The Privacy Act protects information about identifiable individuals.

28. The Privacy Act will continue to apply to data holders, accredited requestors, and outsourced providers, so all personal information remains subject to the requirements of the Privacy Act, except where the draft law says otherwise.

29. Customer data requests under the draft law are similar to Information Privacy Principle (IPP) 6 requests for personal information under the Privacy Act. IPP 6 entitles an individual to access their information, and provides that requests may be made by an individual's representative on their behalf. The intent of the draft law is to more specifically enable access to customer information in a standardised format which can be exchanged and processed by computers, in a safe and secure way.

30. The draft law provides that all customer data requests are IPP 6 requests under the Privacy Act to the extent that they relate to personal information. The process under the draft law is a little different and is intended to make it easier to access customer data. Individuals will still have a right to access their personal information under the Privacy Act.

31. In some areas, the draft law makes it clear that there will be more specific requirements for customer data requests set in standards and regulations, that accredited requestors and data holders will need to follow. This includes, for example, a shorter deadline for providing data to data requestors compared to the 20 working days prescribed in the Privacy Act.

32. The Privacy Commissioner will be able to exercise all their existing functions and powers in relation to personal information under the draft law. This means the Privacy Commissioner will continue to have investigation, guidance, enforcement and redress powers over any obligations in the draft law that relate to Privacy Act safeguards. The draft law sets out that MBIE will separately monitor compliance and enforcement of obligations beyond those which would be covered in the Privacy Act to ensure the integrity of data exchange. See pages 53 to 58 for further details on how shared jurisdiction, and various powers, penalties and liabilities are proposed to work.

33. At this stage, we have only considered Privacy Act interactions for customer data requests. Further consideration of Privacy Act interactions for action initiation under the draft law is required, but we expect it would follow a similar approach to how customer data requests are treated.

34. Adding special requirements for the draft law which do not have an equivalent for personal information more generally would add significant cost and complexity for participants. This will reduce uptake and benefits from using the draft law to exchange data rather than other less efficient and secure mechanisms (like screen scraping) where the draft law will not apply. Further policy decisions that relate to privacy more broadly are more appropriately considered in any future review of the Privacy Act.

Differences from the Australian Consumer Data Right

35. The draft law has similar aims to the Australian CDR, but also has some key differences because we are relying on our Privacy Act. Unlike our Privacy Act which applies across the economy, the Australian Privacy Act 1988 generally applies only to Government agencies and organisations with an annual turnover of more than $3 million. The Australian CDR includes requirements on CDR participants to invest in additional functionality which:

- enables them to delete customer data, on request of the customer. In New Zealand, the Privacy Act’s IPP 7 empowers an individual to request the correction of personal information that is held by them. The Privacy Act does not have a general right to request deletion of personal information, however IPP 9 states that an organisation should not keep personal information for longer than it is required for the purpose it may lawfully be used

- enables customers to remain anonymous or use a pseudonym (eg ‘customer 123’) to minimise the data collected and held about them. In New Zealand, IPP 1 governs the collection of personal information more broadly and already requires data minimisation

- prohibits the use of CDR data for direct marketing. In New Zealand, IPP 3, IPP 4 and IPP 10 govern the collection and use of personal information. A prohibition on direct marketing is not proposed to be included in the draft law at this time because we wish to rely on the Privacy Act wherever possible.

Question 1: Does the proposed approach for the interaction between the draft law and the Privacy Act achieve our objective of relying on Privacy Act protections where possible? Have we disapplied the right parts of the Privacy Act?

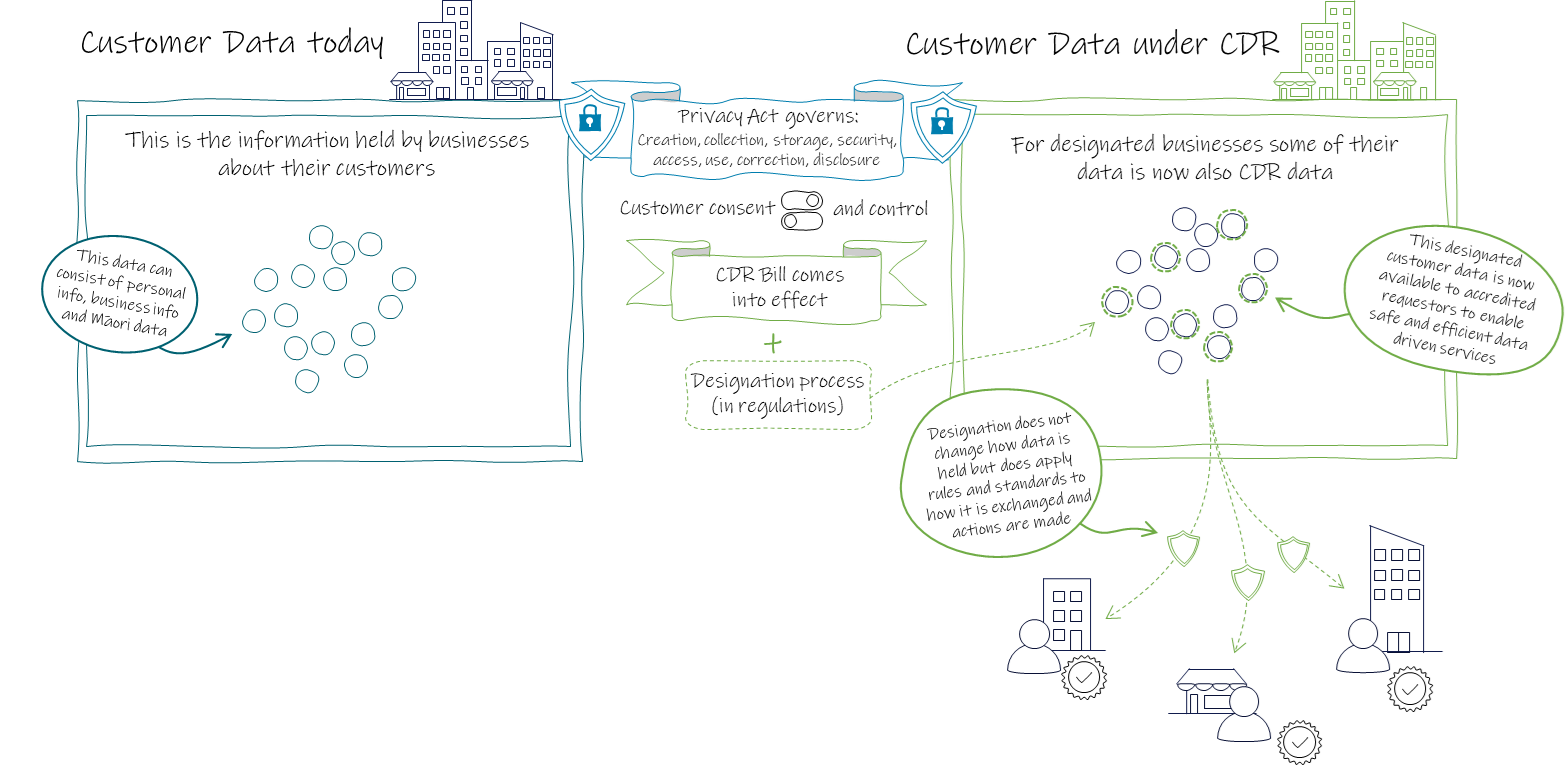

Diagram of customer data today and under the draft law

36. The diagram on the next page illustrates how the draft law’s obligations overlay onto existing data held by businesses:

- business security measures and Privacy Act obligations continue

- designation will identify a subset of existing customer data, subject to the regime

- customer consent and control remain central.

Text description of image

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi

37. The customer data that will be designated by the draft law will hold value and opportunity for all. Within designated customer data, some Māori data[5] will be a taonga (treasure).[6]

38. We consider that the draft law’s requirements, and the overall purpose of the draft law, may be consistent with aspects of tikanga (Māori concepts, practices and values). This is because of the very high value placed by Māori on both:

- safeguarding and protecting data, while also

- ensuring it is used to advance collective and individual wellbeing.

39. We are interested in testing and exploring this.

40. The focus of the draft law is on standards relating to data exchange rather than data sets. However, we also think the draft law could benefit significantly from looking to and learning from the principles and concepts of Māori Data Governance. Again, this is because of the high value Māori place on care for and use of data.

41. As part of seeking feedback on the exposure draft, in questions 13, 15 and 28 we seek feedback on:

- how a Te Tiriti/Treaty and te ao Māori lens could strengthen the processes and decisions required in the draft law

- the detailed design of the draft law’s requirements and implementation

- the opportunities or risks that the implementation of the draft law could present for iwi, hapū and Māori individuals, businesses and organisations.

42. The draft law will apply to Māori data, even where it is not identifiable as such. Tikanga associated with data governance practices may be relevant to design of the draft law’s regulations, standards and user interfaces.

43. There will be relationships between the articles of Te Tiriti/the Treaty, tikanga relating to data governance and use, and elements of the draft law (respect, care, trust and unlocking value). We are interested in feedback on these. There are strong linkages also with the Māori Data Governance Model developed by Te Kāhui Raraunga[7] and we will be working to identify these now that this model has been published.

Other linkages and alignment

44. The draft law is aligned with elements of existing legislation (eg the Digital Identity Services Trust Framework Act 2023 (DISTF Act), and Accreditation and Standards Act 2015 where possible. We will also continue working to align with other work, including the Single Customer View requirements being developed under the Deposit Takers Bill, and work under the Retail Payment System Act 2022.

45. The draft law is informed by the Australian Consumer Data Right legislation – both the existing law and the proposed amendments currently before the Australian Parliament. To support interoperability of the two systems, the draft law:

- provides that consistency with international standards is a consideration in the development of any binding standards relating to data exchange

- limits the requirements relating to action initiation to accredited requestors and designated data holders

- enables the setting of accreditation criteria similar to those in Australia, the United Kingdom.

Proposed scope

46. The draft law will:

- apply to the entire economy, but will be turned on gradually through designation regulations (identifying particular data holders, product data and customer data)

- apply to designated customer or product data held by those carrying on business in New Zealand irrespective of where data is collected or held, or where the customer or product concerned is located (see territorial application on page 44 for more detail)

- apply to the Crown. Data held by government can be designated into the system.

47. Using the new system is opt-in for customers. The draft law requires that customers who opt-in can withdraw their consent at any time.

Out of scope

48. The draft law does not seek to change broader legal settings regarding:

- other methods of sharing data (eg screen scraping)

- the use or on-sharing of personal information or other information

- collection, storage, security of personal information or commercial information

- data ownership or geographical location of where data is stored.

49. The intention is for these to be governed by existing, economy-wide requirements to minimise compliance costs and encourage uptake of secure data services regulated by the draft law.

50. The draft law does not require customer data to travel via government agencies when it is exchanged. These exchanges happen directly between a data holder and accredited requestor once the necessary safeguards are met.

51, The draft law does not create any additional powers for the government to collect, share or view people’s customer data or business information.

52. The draft law relates to existing data already held by product and service providers. It does not require the creation or collection of new customer data.

Footnotes

[5] Māori data is data that is produced by Māori, or that describes Māori and the environments they have relationships with. Hudson, Anderson, Dewes, Temara, Whaanga and Roa (2017) "He Matapihi ki te Mana Raraunga” - Conceptualising Big Data through a Māori lens. In Whaanga, Keegan & Apperley (Eds.), He Whare Hangarau Māori - Language, culture & technology (pp 64–73). Hamilton, New Zealand: Te Pua Wānanga ki te Ao / Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies, the University of Waikato, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/11814(external link).

[6] The data which becomes designated will likely have high value, will almost always have multiple uses, and we expect it will hold significant opportunity, thus meeting the criteria outlined by Hudson et al (2017), in footnote 5.

[7] Māori Data Governance Model (May 2023), Te Kāhui Raraunga, https://www.kahuiraraunga.io/tawhitinuku(external link).