Annex 3: International models for offshore renewable energy regulation

On this page

Internationally, governments have adopted different approaches for regulating offshore renewable energy, in particular wind energy. There are key choices as to the role of government in conducting feasibility activities, and when to grant exclusivity to developers. Governments have taken different approaches to these choices and have evolved their approaches over time.

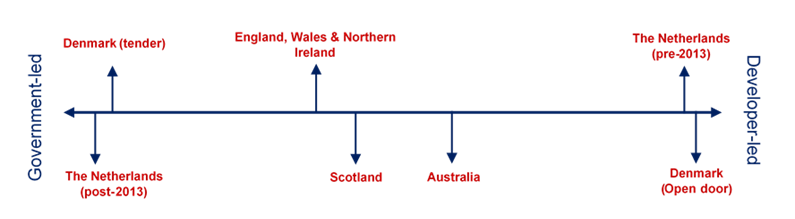

Figure 4. Continuum of international approaches to assessing feasibility for offshore renewable energy

Image transcript

In the early stages of an industry’s development, a key question is how to identify potential areas for development and what role government should play in this. The degree of government involvement also tends to inform the point in the development cycle at which developers are granted exclusivity. This is either done at the feasibility stage or prior to construction and operation.

Usually when developers take-up responsibility for feasibility assessments, and incur the associated costs, they also seek site exclusivity. Exclusivity is the agreement that only one developer can conduct feasibility assessment in a given site, and (potentially) proceed to construction and operation. Exclusivity can be granted through instruments such as leases, options, permits, or licences.

The regimes operating in the Netherlands, Australia, Denmark, and the United Kingdom show how countries have taken different approaches to these questions.

The Dutch model

Although today the Netherlands is a leader in cost-efficient offshore wind development and installation, only a few offshore wind farms were built in the Dutch Economic Zone of the North Sea until 2017. This is often attributed to the fact that project developers were responsible for site selection and investigation, as well as having to go through the permitting process for projects with no guarantee projects would be approved – facing high costs and risks. However, in 2013, amidst accelerated climate ambitions and the start of the Dutch energy transition, the Government changed their approach and committed to assigning and developing offshore wind zones in the Dutch sector of the North Sea.

Dutch Offshore Wind Guide [PDF 13.1MB](external link)

Since 2013, the Dutch Government has used a National Water Plan to designate areas for offshore wind energy deployment. In a more proactive approach than before, the government selects locations in these areas, and specifies conditions of construction and operation. Environmental and conservation assessments are performed. The government also performs specific studies about wind, soil and water conditions in order to determine construction and operation conditions. Based on the outcomes of these assessments and studies, a private developer is selected by a tender process to construct and operate the project.

Wet windenergie op zee(external link)

The government can recover the costs of these assessments and studies from the party who is granted the permit.

The Australian model

Australia has followed a similar process to Scotland, except it does not have a marine spatial plan. Instead, Australia’s Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 provides for the Minister for Climate Change and Energy to declare areas that are suitable for offshore renewable electricity infrastructure.

Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021, Part 2(external link) — Federal Register of Legislation Australia

In deciding whether an area is suitable for offshore renewable energy infrastructure, the Minister must have regard to the potential impacts of the construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance or decommissioning of offshore renewable energy infrastructure in the area on other marine users and interests. The Minister must also have regard to any submissions received as part of the mandatory consultation process on proposed declared areas; Australia’s international obligations in relation to the area; and any other relevant matters.

The Government of Australia has recently proposed an area in the Commonwealth waters off Gippsland, Victoria for offshore renewable energy projects.

Offshore renewable energy infrastructure area proposal: Bass Strait off Gippsland(external link) — Consultation Hub

Consultation on the proposed area included a non-exhaustive list of identified users and interests to facilitate conversations about the suitability of the area.

Marine Users and Interests Gippsland, Victoria [PDF 586KB](external link)

These included:

- Native title – developers need to understand their obligations if land-based transmission infrastructure is proposed.

- Commercial and recreational fishing – developers will need to undertake consultation with the local community and demonstrate how they will share the area with other users and will also need to have a plan for gathering and responding to ongoing feedback from stakeholders throughout the life of the project.

- Natural environment – matters of National Environmental Significance, such as the Orange Bellied Parrot, Pygmy Blue Whale, and threatened Albatross species are identified. Developers need to seek relevant environmental approvals to proceed.

- Existing oil and gas titles and infrastructure – developers need to undertake consultation and demonstrate how they will share the area with other uses and have a plan for gathering and responding to ongoing feedback from stakeholders throughout the life of the project.

- Tourism – developers need to assess how projects could affect participation in tourism and recreation.

- Defence – consultation with the Department of Defence is required in relation to Defence Practice Areas.

- Vessel traffic – high volume shipping channels, including traffic separation schemes, are excluded from the area.

- Weather radars – developers need to work with the Bureau of Meteorology to mitigate any service impacts.

Developers select the boundary and size of specific sites and apply for feasibility licences, which can be granted for a period up to 7 years.

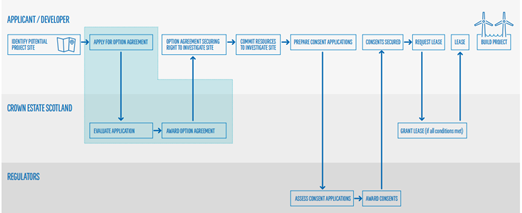

Figure 5. Australian offshore renewable energy infrastructure development process

Source: Australian Government: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

Image transcript

The United Kingdom model

The United Kingdom, which has the largest installed offshore wind generation globally, operates a 4-stage leasing process to grant exclusive leases for exploration and feasibility assessments.

Seabed leasing for existing offshore wind farms has been managed by The Crown Estate through several leasing rounds that began in 2000. In 2017, a new body, Crown Estate Scotland, was formed to own and manage the seabed in Scottish Territorial Waters and adjacent areas of the United Kingdom Exclusive Economic Zone. The Crown Estate retains responsibility for the seabed in England, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Before the consenting process can begin, the developer must secure a seabed lease from The Crown Estate or Crown Estate Scotland. Leases are granted through a competitive tender process following the identification of broad areas for development.

The exact process for obtaining for leases and consents varies across the United Kingdom. In England, a Development Consent Order is granted under the Planning Act 2008 which incorporates a number of consents, including a marine licence and onshore consents. Whereas in Scotland, Marine Scotland examines applications for the offshore works and Scottish Ministers grant or refuse consent. However, the general process for seabed leases remains the same across the United Kingdom (as described below). (World Bank Group, Key Factors for Successful Development of Offshore Wind in Emerging Markets, 2021, p.49.)

Stage 1

Consideration (3-4 months)

Aim: The aim of this stage is to ensure potential bidders have all the information required to understand the process and clarify requirements.

Typical steps: The leasing body provides all relevant competition information of the market, including objectives, process, timeframes, and rules for the competition.

This may include the leasing body hosting market information days, providing potential bidders an opportunity to ask questions, and directly engaging with the leasing body.

Stage 2

Prequalifications questionnaire (PQQ) (5 months)

Aim: The aim of this stage is to filter the number of potential bidders and ensure that only those with the relevant capabilities submit bids.

Typical steps: The leasing body issues a PQQ to the market.

Potential bidders respond to the PQQ, and the leasing body assesses the potential bidder's financial capability, technical experience, and legal compliance.

Successful bidders prequalify to the next stage of the competition.

Stage 3

Intivation to tender (ITT) (1 month)

Aim: The aim of this stage is to evaluate tender submissions against competition requirements.

Typical steps: The prequalified bidders are invited to submit a tender.

The tender is evaluated by the leasing body via an assessment of the financial and technical robustness of the bid.

The tender process may be multistaged.

Winners are notified and progress to the next stage.

Stage 4

Agreement for lease

Aim: The aim of this stage is to secure an agreement (or option) for lease with the winners of the competition. This agreement provides the winner with exclusive development rights to an are of seabed, thereby providing the security required to invest in the project's development.

Typical steps: Winning bidders proceed to negogiate the details and terms of the lease with the leasing body.

Following negotiation, a lease is awarded and signed by both parties.

The agreement is conditional on a project receiving all necessary permits.

Figure 6. Offshore renewable energy infrastructure development process in the United Kingdom

Source: World Bank Group

Image transcript

The Danish model

In Denmark, the establishment of offshore wind turbines can follow a tender procedure run by the Danish Energy Agency or an open-door-procedure. Most new offshore wind farms in Denmark are established after a tendering procedure. The Danish Energy Agency will operate a site-specific tender for an offshore wind farm, of a specific size, eg 200 MW. The site is awarded on the basis of the price the developer offers for producing electricity.

In the open-door procedure, the project developer takes the initiative to establish an offshore wind farm. The project developer submits an unsolicited application for a license to carry out preliminary investigations in the given area. The application must, as a minimum, include a description of the project, the anticipated scope of the preliminary investigations, the size and number of turbines, and the limits of the project’s geographical siting. In an open-door project, the developer pays for the grid connection to land.

The Danish Energy Agency initiates a hearing of other government bodies to identify whether there are other major public interests that could block the implementation of the project before the Danish Energy Agency processes the application. Based on the result of the hearing, the Danish Energy Agency decides whether the area in the application can be developed, and in the event of a positive decision it issues an approval for the applicant to carry out preliminary investigations. If the results of the preliminary investigations show that the project can be approved, the project developer can obtain a licence to establish the project.

< Annex 2: Proposed resource management reforms | Annex 4: Aotearoa New Zealand’s international obligations >