Describing who and what shaped this strategy

On this page

How we created this strategy

Input and collaboration across MBIE was essential to developing this strategy.

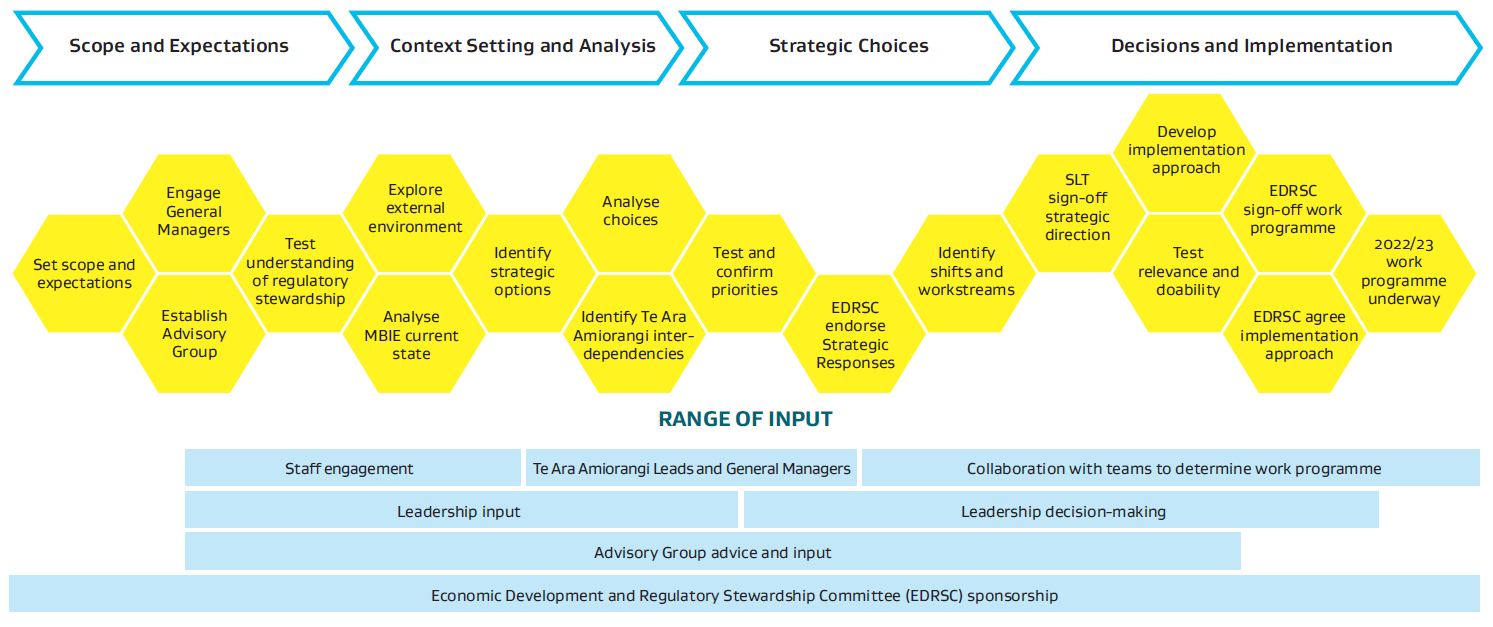

The diagram below shows how the different perspectives, experiences and voices from across MBIE were brought together to inform and shape this strategy in 2022.

Continued dialogue across MBIE will be critical for the strategy’s implementation – to inform and refine the work programme, track implementation, and measure the impact as we all work towards embedding stewardship.

Process and inputs to develop this strategy in 2022

Text in image

MBIE’s stewardship journey and lessons learnt

MBIE began its regulatory stewardship journey in 2013. This strategy builds on what we’ve learnt and achieved since then.

Stewardship is a public service responsibility

The 2013 amendment of State Sector Act 1988 formalised the role of stewardship in improving regulation by describing chief executives’ responsibility to steward their organisations, assets, liabilities and legislation.

The value of a stewardship approach for regulators was reinforced by The Aotearoa New Zealand Productivity Commission’s 2014 Regulatory Institutions and Practices report. It reviewed where and how to make improvements in the quality and effectiveness of government regulatory institutions and practices. In the same year, MBIE’s Performance Improvement Framework review challenged MBIE to enhance its regulatory stewardship role.

Regulatory stewardship is now a firmly established good practice expectation for public service agencies through the Public Service Act 2020 and through the Minister of Finance’s Letters of Expectation.

MBIE defines its role as working in regulatory systems

Since 2013, MBIE has increasingly invested in regulatory system stewardship. Achievements have included:

- Publishing the 2017 regulatory stewardship strategy which cemented MBIE's understanding of being a regulator and of good regulatory practices

- Hosting the Government Centre for Dispute Resolution (GCDR) to drive improvements to this important regulatory function

- Passing the first two Regulatory Systems Amendment Bills, and making progress on two further bills

- Collaborating with other regulatory agencies to establish and host the Government Regulatory Practice Initiative (G-Reg) to improve regulatory practice through leadership, culture, and workforce capability.

Establishing the regulatory stewardship branch cements MBIE’s commitment to regulatory stewardship

In 2019, the Regulatory Stewardship Branch was established to support a deliberate focus on improving MBIE's stewardship maturity and to support individual systems. With the branch’s support, most systems across MBIE have made some progress to support their system stewardship.

Progress includes carrying out Regulatory System Stewardship Maturity Assessments, creating charters to clarify the objectives and scope of systems, and establishing system governance and risk management approaches. A significant aspect of this progress has been increasing collaboration, not only across MBIE but also with external organisations operating within our regulatory systems.

The Productivity Commission’s 2014 report continues to be an important touchstone. It identified a range of common causes of regulatory failure, and MBIE is working to develop and implement stewardship practices that respond to those potential sources of failure.

The diagram in the Appendix describes MBIE’s regulatory stewardship journey so far, in particular the significant steps towards creating an environment that supports stewardship.

What we’ve learnt about what good regulatory stewardship looks like

The understanding of what regulatory stewardship encompasses is still evolving. One current description states that regulatory stewardship is:

the active governance, monitoring and care of regulatory systems to ensure that all the different parts work together well to achieve intended outcomes and keep the system fit for purpose over the long-term.

Treasury, 2022

Through our work on stewardship at MBIE, we’ve learnt:

- the value of regulatory stewardship as a mechanism for encouraging closer connection between regulatory functions, including policy and operations

- the importance of driving regulatory stewardship through collective system leadership

- what good regulatory stewardship looks like in practice.

We’ve also learnt that regulatory stewardship requires the different parts of our organisation, as well as the external partners in our regulatory systems, to work together well.

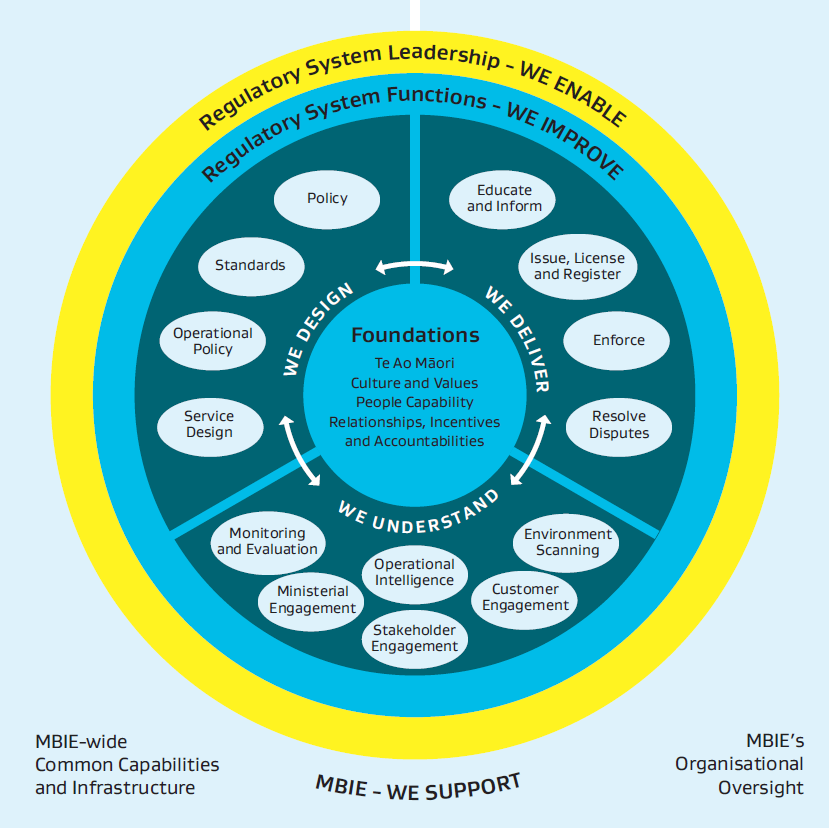

The diagram on the opposite page captures the elements that contribute to high-performing regulatory systems.

- At the heart of these are the Foundations that shape our regulatory mindset, priorities, and stewardship culture.

- Understanding, designing, delivering and improving regulatory systems are essential Regulatory System Functions, where MBIE strives for high performing regulatory practices and a knowledge base to drive decision-making.

- Regulatory system governance enables collective responsibility across MBIE and with external regulatory partners through Regulatory System Leadership.

- Our regulatory roles and practices are shaped and supported by MBIE-wide Common Capabilities and Infrastructure.

- Across MBIE, senior leaders and governance groups provide Organisational Oversight.

Stewardship makes systems more resilient to changes in technology, society and the economy. It both reduces the risk of system failure and strengthens systems’ capacity to improve the lives, work and businesses of New Zealanders.

Paul Stocks

Deputy Secretary Building, Resources and Markets

Elements that contribute to a high-performing regulatory system

Text in image

Stewardship isn’t about excellence in a singular activity — it EMERGES from the interaction between these elements…

Lisa Docherty Director Government Regulatory Practice

and Strategic Initiatives

The opportunities to be better regulatory stewards

MBIE faces challenges and opportunities to ensure our regulatory systems are well-placed to understand and respond to trends that shape the cultural and behavioural norms of New Zealanders. Regulatory stewardship can help address these.

Through the strategy development process, we heard that MBIE faces four high-level challenges and opportunities to achieving high-performing regulatory systems.

We need to explore and understand the changes to the world around us that impact our regulatory systems

The past few decades have been characterised by innovations that have challenged business models and markets, personal and social interactions, and the role of government in regulating markets and social spheres. Ensuring that we can access information to understand how change affects the relevance and effectiveness of regulation is a fundamental part of our stewardship.

The need to better understand the performance of existing regulatory settings sits alongside the need to gain insights about macro trends driving change across Aotearoa New Zealand. Are our current compliance strategies and service delivery designs achieving system objectives, without creating unintended consequences or undermining the effectiveness of adjacent systems? How well placed are we to take advantage of today’s technology to gather and analyse performance information?

Evolving Societal Expectations

Changes such as mandatory seat belt wearing (1970s), car seats for children under five (1994) and banning the use of handheld mobile devices while driving (2009), are examples of changes to regulatory settings that imply a reduction in the public’s risk appetite. On the other hand, there are also regulatory changes that go the other way, suggesting that in these areas, the public perceive a lower risk (or have become more accepting of the risk) than previously (eg, lowering the age to purchase alcohol from 20 to 18 in 1999).

Significant regulatory change in response to major harm or tragedy events reflects a shift in societal expectations, social licence, and risk appetite once a risk has actually happened. Often, the underlying risk hasn’t necessarily changed but the public’s tolerance of that risk has. For example, the geothermal activity risk profile of Whakaari White Island has not changed since December 2019. However, the awareness of the risk is now far higher, and acceptance is much lower now that significant harm has been experienced and is no longer seen as a theoretical risk. If the social licence that underpins a regulatory response is eroded, this may result in lower levels of compliance and reduce the impact the response may otherwise have had.

Questions for Aotearoa New Zealand’s 21st Century Regulatory Stewards

Our understanding of what is most significant for the future shape of our country and the challenges facing Aotearoa New Zealand’s regulators is shifting.

- How does regulatory stewardship give effect to a Māori-Crown Partnership?

- What does regulation that genuinely serves the needs of our diverse communities look like?

- How do we build a more insightful public conversation about the way regulation deals with harm or the potential for harm?

- How do we achieve inclusive co-design of regulation with the community, while meeting demands for quicker adaptation of regulation to changing circumstances?

- How do we develop greater insights into the drivers of regulatory system performance?

- What are the critical features of regulatory systems which make them more resilient to continuing stress and unexpected change?

- What are the opportunities to use emerging technologies to make regulation more effective?

- Where do we most need to develop international regulatory cooperation to make our regulatory systems more effective?

Mark Steel

Director Regulatory Stewardship

We need agility to respond to new developments that create opportunities to do things better

Greater, and faster, flows of information will increasingly test our ability to understand the impact of regulatory settings and to react and respond in a timely way. Keeping pace with, and anticipating changes to, our context is not only important to maintain the relevance of our regulatory systems, but also to shape how we exercise our regulatory role.

There are many opportunities to re-shape our operating and engagement models and evolve the way our regulatory functions interact with Aotearoa New Zealand’s businesses and people, to enhance accountability and maintain engagement. For example, exploring the effectiveness of new modes of communication that reach digital native generations, without exacerbating digital exclusion for other communities and groups.

We need to work together to tackle gnarly issues, fundamental shifts, and emerging opportunities

Working together within systems

We’ve learnt that regulatory systems are more than the sum of their parts and require connection and collaboration between individual functions and organisations. This means we need to place greater value on collective leadership and collaboration within our systems to enable better understanding of the impact of individual functions. Collective leadership will, over time, support more effective regulatory and implementation design, focused on outcomes and risk mitigation.

Working together across systems and across MBIE

Some of the challenges and opportunities we’re facing today are not only moving at pace but are also broader than any single regulatory system. For instance, giving effect to Māori-Crown partnership within our regulatory systems or responding to climate change. Working collectively across MBIE – rather than addressing these issues separately within each system – will provide the knowledge, capacity and efficiency that’s more likely to provide coherent, joined-up responses across systems.

Working together internationally

Many of the trends affecting Aotearoa New Zealand have international elements and drivers which need an international approach to regulation. International regulatory challenges include disruptive, technology enabled business models, the reach of major corporations into our lives, the global nature of supply chains, and the fragmentation and manipulation of information and media. These things challenge our ability to understand and manage the effectiveness of regulation from a domestic viewpoint – and reinforce the need to maintain and increase international cooperation.

Finding space for stewardship is hard in the face of immediate pressures and short-term demands

People from diverse roles across MBIE recognise and appreciate the value that a regulatory stewardship approach brings. However, our people face challenges in operating from a stewardship perspective day to day.

We are also aware of a tendency to deal with current demands and issues, such as developing and implementing new policy and legislation. This sometimes results in a 'set and forget' mentality, where existing settings aren’t reviewed once they are put in place. This may be a rational response to capacity pressures and significant policy change agendas. However, an emphasis on the next challenge makes it difficult to find the time and resources to monitor and evaluate current systems, to establish if things are working as intended. Prioritising enhancement and improvement activities tends to occur once a significant problem occurs. Pushing against this cultural norm is a significant stewardship challenge.

For MBIE managers

Senior managers across MBIE recognise that they operate within a regulatory system as a part of their responsibilities for individual regulatory functions. The challenge they face is the capacity and authority to adopt a system leadership role – the need for clarity and resources to support this in already demanding functional management roles.

For individual regulatory functions

People working in the core regulatory functions acknowledge that evidence-informed practice could be strengthened to deepen understanding of system performance.

It’s also recognised that it can be a challenge to collaborate across functions. This is particularly evident for the design process, which would benefit from better connections between policy and delivery functions.

For MBIE’s corporate functions

Professionals working in our corporate functions provide support, and design organisational structures and systems that better enable regulatory stewardship. How well they can do this will depend on their understanding of regulatory stewardship and how critical it is to the performance of MBIE’s regulatory systems.

Kaitiakitanga is guardianship, caring for, protection, upkeep. We need to actively adopt this mindset and use it to shape our practice as we steward the regulatory systems entrusted to MBIE as kaitiaki.

Melanie Porter

Deputy Secretary Te Waka Pūtahitanga