Proposed changes to the Skilled Migrant Category

We are proposing to introduce a simplified points system that sets a clear, fair, and transparent eligibility threshold for skilled residence.

On this page

Simplified Points System

Proposed future points system

Read the data for this table

We are proposing to introduce a new, simplified points system. The simplified points system sets a clear skill threshold for residence and offers several ways for people to demonstrate their skill level.

A key choice is how tightly to target the skill level:

-

Setting a higher skill level supports a higher-wage, higher productivity economy, and helps to manage numbers within New Zealand’s absorptive capacity.

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Immigration describes absorptive capacity as a broad concept, covering physical infrastructure (like transport, communications), land supply and housing infrastructure, core public health and education services, and broader community infrastructure.

People at higher skill levels tend to be more able to transfer skills if the labour market changes. However, if the skill threshold is set too high, employers can struggle to attract the appropriate skills and experience to supplement the domestic workforce, meaning economic growth can stagnate.

-

Setting a lower skill level provides employers and migrants with certainty and avoids creating a large population of people onshore without a realistic pathway to residence. However, if the skill threshold is set too low, it can lead to wage stagnation, reliance on low-wage migrant labour, and limited incentives for employers to invest in improving productivity through investment in higher skill levels and technology.

Under the simplified points system, the eligibility threshold is set at equivalent to six years of “human capital”. This means it would take at least six years for someone in the domestic workforce to gain that level of education, training and/or work experience. This is consistent with the focus on granting residence to people who can fill medium- to long-term skill needs that would be hard, or take time, to fill from the domestic labour market, even under the right conditions.

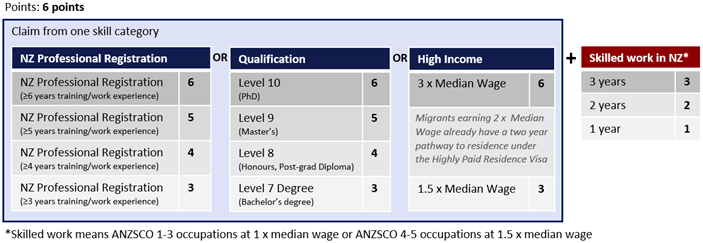

Applicants must have at least 6 points to be eligible. This can be made up from:

- 3 to 6 points based on professional registration, qualifications, or income. People can choose the skill category that offers the most points based on their circumstances; and

- 1 point per year of work in New Zealand in a skilled job, up to a maximum of 3 points.

As set out below, people working in a small number of occupations identified as presenting immigration and labour market risks will need to meet a higher income threshold to be eligible to apply. This is consistent with the higher income threshold for lower-skilled roles (ANZSCO level 4-5) under the current (and proposed) points systems.

Details of the proposed simplified points system, including examples of how simplified points system would apply, are set out in the next section.

Simplified points system in depth

What about bonus points?

“Keeping it simple” means that the Skilled Migrant Category no longer offers bonus points for non-skill factors such as location, study in New Zealand and partner credentials. This helps to set a clear skill threshold: under the current points system bonus points can act to “discount” the skill level a migrant needs to demonstrate.

In many cases the policy objectives behind these bonus points are better achieved in other ways. For example, under the current system points for employment outside the Auckland region are equivalent to six years of skilled work experience, but evidence shows it has not had the intended impact of increasing migrant retention in the regions. Incentives outside the immigration system, such as wages, employment conditions or lifestyle are likely to have more impact in attracting people to the regions.

Who will miss out on residence?

As set out above, the proposed changes aim to give migrants certainty about who will be eligible for skilled residence. We cannot definitively say that specific occupations will miss out under the proposed settings, because the Skilled Migrant Category focuses on individual skills and characteristics (unlike the Green List, which is occupation-based). However, it will be more difficult for migrants in some occupations to meet the points threshold, especially where training is primarily on-the-job and there is no associated registration scheme.

Following consultation, we will provide further advice to the Government on critical roles that do not meet the criteria for the Skilled Migrant Category and options to address them. To keep the points system simple, the Green List is likely to provide the best avenue for any occupation-based exceptions. The Green List will, however, remain tightly focused on occupations of critical importance to the New Zealand economy. A review of the Green List is planned for July 2023, around the same time as the new Skilled Migrant Category settings are expected to be introduced.

What other options were considered?

We also considered:

-

A time-based system, which would grant residence to people that have worked in New Zealand for a period, e.g. five years, on the basis that the length of time worked demonstrates a medium-term skill need. This option would minimise (or eliminate) the number of people onshore without a pathway to residence. However, it would limit our ability to manage residence numbers, unless the threshold for temporary work visas was increased. For higher-skilled migrants, the length of time required to work before gaining residence could potentially put them off, particularly if comparable countries provide faster residence pathways. Instead, the simplified points system enables people to claim time worked in New Zealand to meet up to half of the points requirement.

-

An income-based system, which uses an income threshold, e.g. 1.5 times median wage, as the only proxy for skill. Income is already used as a threshold for the Accredited Employer Work Visa and to provide a residence pathway for highly paid migrants. This option would lead to a lower number of people eligible for residence. Some highly skilled occupations that are highly skilled but comparatively not as well paid would likely miss out (e.g. qualified trades, teachers, some health sector workers such as physiotherapists, and social workers). It may also reflect or embed structural pay issues (e.g. pay parity/discrepancies across gender and ethnicity lines). Instead, the simplified points system builds in income as one way of demonstrating skill.

Questions

The key proposal is to introduce a new, simplified points system. It focuses on granting residence to people who can fill medium- to long-term skill needs that would be hard, or take time, to fill from the domestic labour market, even under the right conditions.The key proposal is to introduce a new, simplified points system. It focuses on granting residence to people who can fill medium- to long-term skill needs that would be hard, or take time, to fill from the domestic labour market, even under the right conditions.

3. Do you agree with the proposed skill threshold, i.e. equivalent to six years formal training and/or skilled experience? Why/why not?

4. Do you agree that a points system using a range of skills proxies is a clear, fair way to assess Skilled Migrant Category applications? Why/why not?

5. Do you have any other comments on this section?

More questions on the proposed simplified points system are in the next section.

How many people will gain residence under the proposed settings?

The benefits of managing the flow of migrants into New Zealand are:

-

It helps population growth to remain within New Zealand’s capacity to absorb people, to avoid putting unsustainable pressure on New Zealand’s long-term housing, infrastructure, and social services.

-

It maintains tension in the labour market to encourage employers to lift wages and conditions and shift to more productive business models, rather than relying on access to large numbers of migrants.

Pre-COVID, the number of Skilled Migrant Category visas approved every year was managed under a “planning range”. The Government would agree to an overall number that covered all residence class visas under the New Zealand Residence Programme. Although not a formal cap, the planning range acted to limit the number of people granted residence annually. This approach enabled Immigration New Zealand to commit sufficient processing resource to deliver the agreed number of approvals. In practice, the number of eligible applications significantly exceeded the planning range. For example, as set out above, in 2019 only 40 per cent of eligible residence applications were processed and approved. This resulted in a large backlog of applications and long wait times for decisions. In 2018, the Government agreed to move away from planning ranges beginning in 2020, but COVID impacts meant that a new approach was not implemented.

Under the proposed new settings, there will be no cap on the number of eligible applications that can be processed. Immigration New Zealand will adjust its resources based on forecasting and process “to demand”, as it does for temporary visas. The move away from a numerical limit relies on setting an appropriate skill level to help manage demand.

Application Process

We are proposing to remove the step where people need to submit an Expression of Interest (EOI) before being invited to apply, i.e. people can go straight to the application stage. The EOI process is primarily used to help manage numbers under the planning range, which would no longer be relevant under the proposed system where all eligible applications can be processed.

Expected migrant flows

If migrant flows return to pre-COVID levels, a higher number of people are expected to gain residence every year under the proposed settings, even with a tighter skill threshold than the current points system.

MBIE estimates that the simplified points system would result in around 26 per cent fewer applications being submitted. However, approximately 14,500 of the 19,750 applications submitted would be eligible across the skilled residence pathways (Green List, Highly Paid (twice median wage) pathway and a simplified points system). This compares to 8,150 actual approvals in 2019.

This does not mean higher overall migrant flows, but rather that, combined with the introduction of the median wage threshold for Accredited Employer Work Visas under the Immigration Rebalance, a higher proportion of people on temporary work visas will move to residence.

Over the next few years, the number of people coming through the Skilled Migrant Category is expected to be relatively low, because:

-

most onshore migrant workers gained residence through the one-off 2021 Resident Visa

-

under the proposed future settings most new migrants will need to spend some time working in New Zealand before becoming eligible.

Monitoring of migrant flows

In place of a planning range, MBIE will monitor the settings and adjustments may be made if e.g. the number of approvals is higher (or lower) than expected, or the types of skills are not well-aligned with New Zealand’s long-term needs. The monitoring framework will be developed following final decisions on the proposed changes. Consideration will be given to factors such as net permanent and long-term migration, as well as significant shifts in immigration patterns or labour market demand. A response could be either a policy response, e.g. changes to the eligibility criteria, or an operational response, e.g. streamlining of processes or adjusting processing resources if appropriate.

Work on a monitoring framework for migrant flows may also feed into broader, whole-of-government consideration of population issues, including in response to the recent Productivity Commission Report on Immigration.

The Productivity Commission Report recommends the Government develops a Government Policy Statement that includes how the demand for temporary and residence visas will be managed, taking account of significant pressures (if any) on New Zealand’s absorptive capacity.

Questions

Under the proposed new settings, there will be no cap and all eligible applications can be processed annually. This relies on setting an appropriate skill level to help manage demand. The settings will be monitored and adjustments may be made if the number of approvals is higher (or lower) than expected.

6. Do you agree with the proposed approach to managing migrant numbers? Why/why not?

7. Do you have any other comments on this section?

What about people who are not eligible for residence?

There are currently no restrictions on the amount of time someone earning over median wage can spend in New Zealand on a temporary work visa. This created a population of people onshore who were able to become well-settled, but who had no realistic pathway to residence. A significant proportion of these people will gain residence through the one-off 2021 Resident Visa, but we want to avoid growing this population again.

Becoming well-settled without a pathway to residence can create a range of negative impacts for migrants, including:

-

The longer people live in New Zealand, the more difficult and less desirable it can become to return home. This means people can effectively become de facto residents, but without the rights and protections that go along with residence.

-

Temporary work visas are based on a job offer. This means that if a migrant is injured or ill and no longer able to work, or they lose their job, they lose the basis for their visa and need to leave the country. This can create significant insecurity and vulnerability to exploitation.

-

Temporary migrants don’t have access to the same benefits and government support as New Zealanders, such as the right to vote, to purchase a home, or to access to social security benefits and subsidised tertiary education.

The new median wage income threshold for most temporary workers will reduce the proportion of people without a realistic pathway to residence. However, there will still be a gap between eligibility for temporary work and residence visas. This is appropriate – closing the gap completely by giving residence to everyone eligible for a temporary work visa would mean either:

-

the potential for unmanageably high immigration flows; or

-

a need to increase the threshold for temporary work visas, which is harder and not appropriate in the context of immediate labour shortages.

A stand-down policy is already in place for migrants on temporary visas earning below median wage, where after a maximum period of 3 years they must spend at least 12 months outside New Zealand. In practice, most people who would have been subject to the stand-down would have gained residence through the 2021 Resident Visa. Most people need to earn median wage to be eligible for the Accredited Employer Work Visa, so the stand-down will not apply.

Under sector agreements, which provide limited exceptions to the median wage requirement for people on Accredited Employer Work Visas, stand-down periods will apply to people after a period (up to a maximum of two years). Sector Agreements will allow sectors traditionally reliant on low-paid migrants time to improve working conditions and work on longer-term resourcing. These sectors are care, construction and infrastructure, meat processing, seafood, seasonal snow, and adventure tourism. Many tourism and hospitality roles will also be provided an exemption to the median wage for a limited period.

We are proposing to apply the stand-down period requirement to all migrants on Accredited Employer Work Visas who do not meet the eligibility criteria for residence, including those earning above median wage, to avoid the risks to migrants of becoming well-settled in New Zealand without the rights and protections that come with residence. Consistent with the existing stand-down policy, we propose to set the maximum time at three years.

The change would effectively mean that migrants could not renew an Accredited Employer Work Visa multiple times. Time on a Post Study Work Visa or Working Holiday Visa would not count towards the time in New Zealand for the stand-down requirement.

Under the simplified points system, migrants would have more clarity about their likelihood of gaining residence, meaning that they could make informed decisions about their immigration options from the beginning. Some people may, however, meet the skill threshold within three years in New Zealand, e.g. through gaining a professional registration, higher-level qualification, or through an increase in pay. We intend to do further work on how to accommodate people on a recognised pathway to residence.

For employers, the stand-down would mean that they could not rely on keeping the same person in a role long-term, if they do not meet the criteria for residence. However, it would not affect their ability to recruit other temporary workers to fill immediate needs that cannot be filled from the domestic labour market.

Questions

We are proposing to apply the stand-down period requirement to all migrants who do not meet the eligibility criteria for residence. The stand-down would mean that after a maximum period of 3 years on an Accredited Employer Work Visa, people must spend at least 12 months outside New Zealand. This is to avoid the risks to migrants of becoming well-settled in New Zealand without the rights and protections that come with residence.

8. Do you agree with the proposal to apply the stand-down period, to reduce the risks associated with migrants becoming well-settled without a realistic pathway to residence? Why/why not?

9. Do you have any other comments on this section?