Focus area: Enhancing the skills and talent pipeline

On this page

Context

Integral to the success of the digital technologies sector is access to the right skills and talent at the right time. For many years however, there have been concerns about the availability of skills and what was being done in New Zealand to build the right level and supply of skills, rather than to bring them in through overreliance on immigration.

Border closures caused by COVID-19 reinforced the existing need to invest in domestic skills and build a pipeline of talent in New Zealand that has pathways into and across the sector, and can benefit from high-value jobs that on average have a median salary around twice the national equivalent.[1]

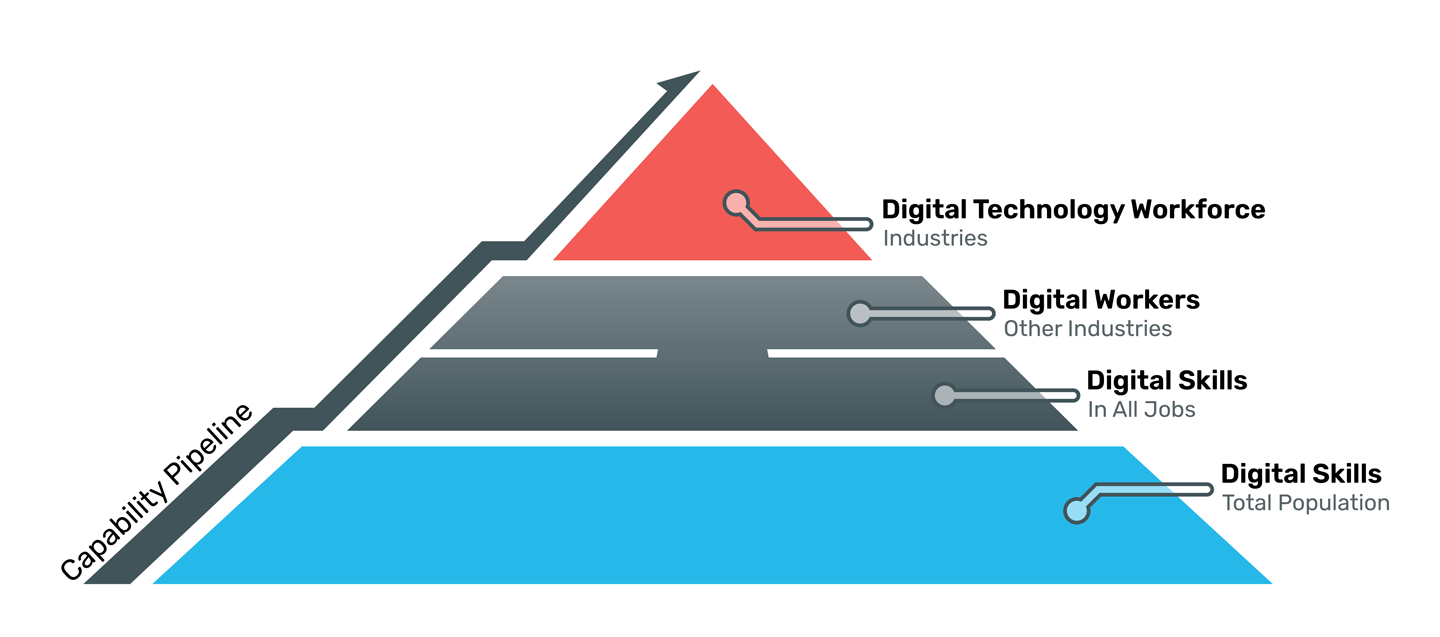

Digital skills in this ITP refers to those skills required to participate in the digital tech workforce (the red triangle in the diagram below).[2] Actions to upskill and reskill workers for this workforce will have spill-over benefits for other industries as well, including those needing workers with technical digital skills such as agritech, advanced manufacturing, construction, fintech, health tech, and food and beverage. Increasingly workers with digital tech skills will be able to move across industries as they traverse their career pathway.

Digital skills in Aotearoa

Text description of diagram

The 'Digital Skills for Our Digital Future' report is a key foundation of this focus area. Based on this report and its significant input, industry developed the 'Digital Skills and Talent Plan (DSTP)', released in October 2021. Both documents confirm a mismatch between supply and demand at various skill levels, a lack of diversity and inclusion, and an overreliance on the immigration system. The sector notes a particular lack of skills in emerging technologies (e.g. AI, cyber security, data science, and blockchain) and in “soft skills” needed to grow and operate digital businesses.

In summary, these issues are driven by:

- misperceptions about digital tech careers and who they are suited for;

- the lack of appropriate and supportive pathways into entry-level positions for youth or those reskilling into digital tech careers;

- insufficient investment in upskilling and career development opportunities for middle and senior staff, which impedes flow through the pipeline to the areas of greatest shortage (e.g. specialist skills, and support for junior staff); and

- low participation rates for under-represented and under-supported groups (such as Māori, Pacific peoples, women, disabled people and the neurodiverse).

The DSTP calls for a rebalancing and investment at various levels to support the sustainable growth of the sector. It outlines initiatives across 10 areas of action that would enhance the skills and talent pipeline, and to address its existing gaps and challenges. It seeks for successful initiatives to be made sustainable for the longer term, and to be scaled up or outwards to benefit other sectors’ skills and talent needs.

This focus area will deliver a targeted implementation of the DSTP initiatives, taking the partnership approach integral to the ITP, and based on coordinated action and investment from both industry and government, working with providers and communities.

For some initiatives, industry and employers are best placed to lead and drive the necessary changes in mindset, culture, and practice to overcome specific systemic challenges. Government can offer incentives and support to assist industry. It can also provide the current system changes in education and vocational training that will enable transformation through pathways that build skills through work-integrated and work-based learning. Government, industry, and providers already have various initiatives underway or in planning, but these need some overarching cohesion to ensure we get the best out of the investment, so that learners, workers, industry, providers and government all benefit.

In its role as government co-lead, MBIE has a facilitation and coordination role for the targeted implementation of initiatives in the DSTP, as well as leading or co-partnering on specific initiatives and activities (particularly those to support industry transformation), or providing direct support (e.g. through funding and other resources).

As part of its role, MBIE has brought together various government agencies and sector representatives who collectively identified three priority areas to implement the DSTP, and the “circuit breakers” needed to address systemic and ongoing issues.

A brief outline follows of the work underway or planned for 2022- 2023 for these three priorities, including activities that started in late 2021. These will be progressed working across government and in partnership with industry, to support an integrated, coordinated and prioritised approach. In addition, they:

- will align with, build on or support other focus areas of the ITP, e.g. the skills development activities for SaaS and the Domestic Tech Story;

- are built on existing system changes underway and funded in the education and training sector (such as the Reform of Vocational Education including the Toi Mai workforce development plan and Regional Skills Leadership Groups’ workforce development plans, the review of NCEA and the refresh of the curriculum, and the implementation of SFIA global skills framework);

- are relevant to existing activity in government and/or industry. For example, the other ITPs (particularly those requiring advanced digital technology skills, e.g. Agritech or Advanced Manufacturing); cyber workforce planning; the Digital Boost’s education resources; the Regional Skills Leadership Groups’ workforce development plans; the Future of Work programme; and

- various employment action plans and strategies, and a variety of projects under those, for population groups such as youth, women, disabled persons, Māori, and Pacific peoples, all of whom are underrepresented in the tech sector. Many have a focus on diversifying the workforce, and addressing systemic barriers, and point to the need for increased capability in digital skills.

Priority areas

Encouraging the discovery and improving awareness of tech careers

The target audiences are children and youth (noting the need to start awareness and interest at the school age), those under-represented in the sector and "career changers", plus whānau, school career advisors, and recruitment and HR staff.

Actions include:

- Leveraging the Domestic tech story.

- Enhancing and showcasing career resources, building on work underway for a new TEC careers platform; Inspiring the Future and IT Professionals' Tech Hub Platform.

Building and enhancing pathways into digital tech careers

Work-integrated pathways and work-based learning are bridges in the "discover-explore-connect" pathway from school to a job (or for adults entering a tech career). They give opportunity to "earn while you learn" and gain skills most relevant to the changing needs of the sector, as well as a swifter pathway into work.

Actions include:

- Developing work-integrated pathway programmes, prototypes and models initially focused at Level 5-7 education and training (including short courses and micro-credentials) and supporting tailored approaches targeted at raising diversity.

- Providing guidance and resources (e.g. playbooks, good practice advice, templates and training) to help employers support staff entering the tech workforce. Implementation of the Skills Framework for the Information Age (see below) will also assist.

- The ITP has a small amount of funding in the 2022/2023 year to support prototypes and projects, and will disseminate insights and resources generated from those. To date, the ITP has supported three initiatives with funding: the initial design stages of (a) a pilot employment programme for dyslexic (neurodiverse) workers, and (b) a framework for a digital tech pathway for Māori rangatahi; and support for a summer internship matching programme for tertiary students.

Growing the maturity and professionalism of the digital tech workforce

Upskilling the digital tech workforce, and reskilling workers across and into the tech sector, will help fill specialist and technical skill needs in greatest demand. Workers can develop skills and experience at the right level and at the right time, and thrive in their roles and professional development.

Actions include:

- Developing a pledge system for employers – an industry-led system with government support and involvement, similar to the UK Tech Charter system.

- Providing employer resources (see above). Initial focus will be given to the SaaS sector to align with the actions for SaaS skills development.

Woven through each of the priority areas are distinct cross-cutting objectives:

- the need to increase and perpetuate diversity in the workforce through specific targeted actions, to increase the proportion of Māori, Pacific peoples, women, disabled persons, and the neurodiverse; and to see more enter and remain in the workforce, as they have the greatest growth potential, and bring distinct skill sets and perspectives to build a thriving industry.

- the implementation of the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) in government, industry and education and training. SFIA is an internationally recognised framework for describing and managing skills and competencies for the tech sector (including sub-sectors such as SaaS and cyber security). It can be used to form the national basis for skills assessment, development, and transfer across providers, pathways, or courses. It can also map and support consistent career development pathways for digital tech workers. In June 2022, MBIE and the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) purchased a three-year country licence for New Zealand. DIA will lead government to implement SFIA, while MBIE and ITPNZ will support industry implementation.

- to grasp the opportunity for government to role model the transformation needed in the digital technologies industry, as it employs a large proportion of the digital technologies workforce and is a significant employer and procurer of digital technology skills and talent. One means of quickly progressing action in this area is through the implementation of SFIA. Agencies could consider increasing support for entry level roles (e.g. graduate programmes such as GovTech).

In addition, the following activities are also priorities:

- establishing a framework such as a revitalised Digital Skills Forum to coordinate and oversee the delivery and results from the implementation of the DSTP, and web-based resource to provide information and guidance for workers, employers, students and trainees, and those considering a job in digital technologies.

- input into immigration policy, so that immigration supplements, not replaces, the skills supply from the domestic workforce.

Inasmuch as the ITP seeks to enhance the domestic supply of skills, and to reduce the reliance on immigration that was evident pre-COVID, there will always be specialist skills that cannot be sourced locally. Immigration will therefore remain important to ensure the tech sector can grow and thrive, by meeting immediate and specific skill needs.

As an interim measure to address immediate skill shortages that border restrictions had created, in February 2022 the government provided a border class exception for the tech sector. As at August 2022, this visa pathway resulted in 52 workers and their families arriving into New Zealand. Since July 2022, tech sector workers have been able to apply for Accredited Employer Work Visas.

Furthermore, the government has since announced several residence pathways relevant to highly skilled digital technology workers: the Green List, which provides a straight-to-residence option for specified tech roles that meet a salary threshold; a 2-year work-to-residence pathway for highly paid migrants paid at or above twice the median wage; and the reopening of the Skilled Migrant Category.

Success factors for this focus area

- The number of jobs in the digital technologies sector grows from 43,750 (in 2022) to over 58,000 in 2030.

- By 2030, the diversity in the workforce has increased significantly. For example:

| Percentage of workforce in 2020 | Percentage of NZ population in 2018 | Target percentage in 2030 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 27% | 50.6% | 50% |

| Māori | 4% | 16.5% | 10% |

| Pacific Peoples | 2.8% | 9% | 6% |

Source: Stats NZ, and 'Digital Skills for Our Digital Future' report

Footnotes

[1] In 2019, industry estimated that the median salary for ICT and digital technology workers was over $92,000, more than 50% higher than the national median salary. Source: Industry self-reporting data. [Back to text]

[2] Diagram supplied by IT Professionals NZ. [Back to text]

< Focus area: Telling our tech story | Focus area: Enriching Māori inclusion and enterprise >